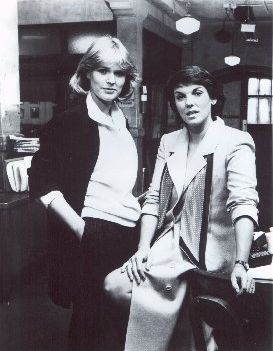

Sharon Gless and Tyne Daly

For transforming "Cagney and Lacey" from a pioneer to a classic, and for making friendship and partnership between women as natural on television as they are in real life. Ms. January, 1987

We were the only family on the block without a television. My father-quick, always, to see the dangers of the new-was ahead of his time in predicting dire consequences of TV; he was not going to have his daughter, whom he was training to be a lady and a scholar, exposed to the idiotic products of diseased minds. On Friday nights we went over to my grandmother's to watch Bishop Sheen. If my father was out of town, my mother and I would stay later at my grandmother's for "I Remember Mama," but we would skulk home in the blessedly concealing dark, built as criminals. When my father died, we moved in with my grandmother, and I took solace in those shows where the mother wore starched house dresses and the father sweaters with elbow patches-but I grew out of that, and since adolescence I have not watched much TV.

All this way is by way of saying that I am in no way a TV junkie. And yet the inviolable hour of my week, the time at which I put down whatever book it is I'm reading, the hour during which if I hear a child crying I respond: "Go call your father, for God's sake," is the hour of ten o'clock on Monday nights, the hour when "Cagney and Lacey" is on TV.

I have always known that "Cagney and Lacey" is created for me. Christine Cagney and Mary Beth Lacey are partner detectives. Now the cop show is not my treasured genre, but "Cagney and Lacey" allows me more identification than anyone could need. Mary Beth Lacey is from my old neighborhood; everyone I grew up with talked like her. She is a woman whose life is shaped by two forces that sometimes threaten to pull her apart; her passionate devotion to her work, and her passionate devotion to her family. Like me, Christine Cagney is an Irish girl who went to Barnard. She owns the sweaters of my dreams. She has a fast mouth that sometimes gets her in trouble. But most important, "Cagney and Lacey" is about two women whose friendship is based on their absorption in their work and their mutual appreciation of each other's skills and talents.

If you ask the people who put "Cagney and Lacey" together and achieved the impossible-saving it from cancellation twice-they will tell you that the genesis of the show is an observation in Molly Haske''s book From Reverence to Rape that there are no women buddy pictures. Cagney and Lacey are buddies-they joke, they fight, both with each other and side by side, they share pizzas and gossip, but they also share the deep recesses of their hearts. When Mary Beth Lacey finds out she has a lump in her breast, it is Christine who overcomes her fearful reluctance to see a doctor. Can you imagine Robert Redford sharing anxiety about a lump on his testicle with Paul Newman? Exactly whose kid is the Sundance Kid? Would Bing come to Bob on the road to Morocco if he were worrying about his father's drinking? Or if her were unsure of the wisdom of settling down with Dorothy Lamour? If we say, then, that "Cagney and Lacey" is the woman's buddy picture, we also have to say that it has redefined the genre. Or created it. It is possible that women are never simply buddies to each other; the female instinct for intimacy is always closer to the surface of the skin. No two women who like each other, who enjoy the significant amount of time they spend together at work, will remain the emotional strangers to each other that the term "buddy" implies.

"Cagney and Lacey" is a weekly embodiment of the richness, pleasure, strength, and liveliness than are found by women in their friendships for each other. It is also a reminder that women who are excellent at their work need not be desexed-or lacking in warmth and humor. What makes "Cagney and Lacey" work is the extraordinary presence of its two stars: Tyne Daly and Sharon Gless-who, both separately and as a team, make "Cagney and Lacey" not a "woman's show," not an "issue" show, but a show you simply don't want to miss. But to say that is to keep back something of the truth. What Sharon Gless and Tyne Daly have done is to provide shimmer in an area that the mythmaking apparatus has swerved widely to avoid, the area of women's friendships.

TV and movies are not the only culprits: the avoidance seems to run through the history of culture. When I was preparing to speak to Tyne Daly and Sharon Gless about what they've accomplished with their characters, I tried to think of other examples of a pair of women heroines who were equals, not rivals, in which one was not in a custodial relation to the other, in which the friendship was not seen as a temporary aberration-like acne-that would go away when the girls achieved their maturity and their real life with men. I could not bring any untainted examples to mind. Think of the pairs of women in literature: Clymenestra and Electra, Antigone and Ismene, Celia and Rosalind in As You Like It, Viola and Olivia in Twelfth Night, Emma Woodhouse and Harriet Smith in Emma, Lorelei and Dorothy in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Eileen and ruth in My Sister Eileen. There is not a pair of equals in the lot.

I can almost see Sharon Gless making a face when she reads this: one of those faces your best friend makes at you when she thinks you're being high-fallutin. Gless doesn't want to hear about what she's done for "the condition of women": she wants to be excellent at what she does. Nevertheless, this woman, who likes to present herself as someone who "gets on with it," is much more thoughtful than her initial presentation suggests. Gless and I met in a restaurant that was called the Tail o' the Cock (the goddess has a sense of humor). I spent a few minutes hiding in the women's room, which was wallpapered with a pattern of important women in history; Queen Victoria, Madama Curie, Catherine the Great. I was scared.

I was determined to avoid what seemed like a predictable "Cagney and Lacey" interview: do you two girls really like each other? I mean, confess: are you really friends in private life? (We don't care about Newman and Redford, after all, in the same way.) I wanted to talk about Gless's achievements as an actress, the kinds of decisions that enable her to create the character of Christine Cagney and to make her partnership with Daly as a fellow actress work.

I had always thought of Sharon Gless in terms of those thirties heroines who make life seem lively and amusing and sharp-edged: Rosalind Russell, Carole Lombard, Irene Dunne. So I began by talking to her about old movies. "I could thread a Bell and Howell projector when I was eight years old," Gless says. Within minutes, we were doing Irene Dunne's lines in "The Awful Truth."

Gless played Carole Lombard in the TV movie "Movieola," which tells the story of the casting of Scarlett O'Hara, and of all her predecessors. Lombard is Gless's strongest influence. "She was full of sunshine," Gless says about her, "full of mischief. She was very confident, and sexy in her confidence. She was also extremely bright; she was the only woman in Hollywood who negotiated her own contracts." Gless smiles. "She also had the filthiest mouth in town."

Why, I asked Gless, aren't there any roles that allow for those Lombard, Rusell, Dunne performances? She had an answer without batting an eye. "Those movies were all based on a caste system which everyone endorsed and at least on that level felt comfortable with. Those women were all aristocrats; they had breeding. You could see it in the way they talked, the way they wore their clothes. Those movies were about the wealthy laughing at themselves."

In a sentence, Gless had solved a problem that had plagued me for years and could have absorbed a women's study seminar for probably a good half semester. All right, I thought, she's smart, we're on. Christine is a character, I say, whose flaws are obvious; she's arrogant, hot tempered, impulsive. How do you make her both lovable and flawed? "I've molded Christine into the woman she is today," she says, with the craftsman's sense of proprietorship. "At the beginning of the show, Chris was more uptown and cool, unflappable. I changed that. Remember, she was raised by a man, a father who adored her. Fighting in a man's world isn't always difficult for her; she likes it." Gless gets that impatient, cut-through-the-nonsense Cagney look. "I won't preach about what shits men are. I will not take the position that men are always the bad guys. It's so boring. And I won't have her endlessly suffering. She's not a victim. God, am I sick of victims."

"But Christine suffers" I say, reminding her of a scene in which Christine discovers that a man she has deeply loved, and yet refused to marry, is going back to his ex-wife, and cannot be there for her when she needs him. The changes on Christine's face were a heartbreaking and masterful evocation of shocked sorrow. "You see what I mean," says Gless. "Christine didn't talk about it. She got on with it. Sure, it felt like hell; she'll probably never have another love in her life like that, it made her feel old and scared and alone, but she got on with her life."

I ask her if she thinks this "getting on with it" aspect of both Christine and herself is a facet of begin brought up identifying largely with men. Were the men in her childhood more important than the women? "Yes," says Gless," I really liked my brothers. I played ball with them, played hard. Sometimes I won. My grandfather really loved me, because I was outspoken and I went after what I wanted. 'I like that kid, that kid's got stuff,' he'd say about me." Her pleasure in the compliment is incandescent. What advice did your mother give you, I ask her later. The tough lot comes back. "My mother said, 'Save yourself for your wedding night," she says.

I ask Gless if there are limits to her one-of-the-guys approach to life. "Sure, there are limits," she says. "I'll tell you a story. In the episode we did when Chris sleeps with the disabled man, the man undresses me. Well, I'm a nut about modesty. So I had this camisole on-Chris doesn't need a bra, right? But underneath it I had on a body stocking, which was supposed to stay on. The actor in pulling down the camisole mistakenly pulled down the body stocking, too, so that my left breast was exposed. Now I have a very raunchy, funny relationship with all the guys on the crew, so they just started whistling and laughing and saying 'All right, Gless!' I just got tough and raucous back with them. Then I went into the women's room and burst out crying, leaning over the sink. The director, who was a woman, followed me. She understood at once what I was going through-that terrible sense of exposure."

Gless's professional triumph, I remind her, is in her acting partnership with the exceedingly strong Tyne Daly, a partnership that never shreds itself into scene stealing, one-upmanship, or the consistent domination of one party. What decisions, I ask, does she have to make in working as an equal with a female, rather than a male, partner? "With a woman," she says, "you have to be more sensitive to sharing. When you're acting with a man and you're the only woman, you can really go full out, really show off. But with another woman-the two actresses have to complement each other; they are more responsible to each other. We have to be aware, for example, that we can't duplicate each other, in gestures or mannerisms." She smiles that dazzling smile. "I think we're pretty good at it."

Tyne Daly is forthright and welcoming in her greeting, but her mind is somewhere else; she's working. I watch her filming a scene that will last perhaps two minutes. The actors rehearse it a half dozen times. I notice Daly trying out nuances of facial expression and gesture; I see her gradually putting together the final package; the pleasant smile that really means "Watch out. I'm reasonable, but I'm dead serious." The movement that blocks the man when he tries to leave. The pacing of the dialogue. "Fine," says the director, "it's a wrap." "No," says Daly, "let's try it again." No one demurs; the director's and the crew's respect for her is palpable. She does the scene three more times. "You're right," says the director, "it's better." "Thank you, gentlemen," she says, and disappears.

The next day when I see her on the set she is holding her one-year-old daughter, Alyzandra. Daly and her husband of 20 years, the actor and director Georg Stanford Brown, have two older daughters, one in high school and one in college. I show Tyne pictures of my children. We chat about babies. Then she is called to the set. The shutter clicks; she is a working actress again; the life outside the work is closed away.

Daly and Gless are rehearsing a scene in which they must warn an anti-apartheid activist against plans that include violence. At one point in the scene, a South African woman tells Cagney and Lacey her story. She was imprisoned for attending her husband's funeral, and her small son's head was broken open by police. They stitched the head up without anesthetic; in her prison cell she heard his cries.

I watch this extraordinarily powerful scene, acted by three women and one boy. My attention is one the faces of Daly and Gless. When the South African woman first approaches them, Gless plays Cagney as cynical and bored; she's a cop; bleeding-heart stories aren't her turf. But as the child takes off his hat and shows his scar, Christine Cagney's face undergoes one of those transformations that break up a life. Daly's Mary Beth is horrified form the first; as she sees the physical evidence of brutality, her horror turns to pained empathy. The actresses never meet each other's eyes. They don't need to.

I am having a very good time. I'm not upset when Daly's publicist sends her apologies. Daly will be a little late; it's her daughter's first day at college and she's just telephoned. Finally, I am shown to Daly's trailer. She apologizes for keeping me waiting; tells me about her daughter's day. The talk turns automatically to children, to Daly as a mother, most importantly to Mary Beth Lacey as a mother. I ask if she thinks Mary Beth is a good mother. "I don't know if she's a very good mother. I don't think she's supermom. That's the importance of her. She's like a lot of us; she's a better mother to one kid than the other. She and Harvey Jr. have a very prickly relationship; I think that's because she was young when she had him, and unsure; things were harder with work, with Harvey; she wasn't entirely ready for him. Michael is her love; in some ways she's afraid for him to grow up. Having daughter is a whole new thing for her. At the same time, she's older with this baby, she's more tired, less carefree. The job is pinching on her heart more-a baby softens the heart, you know, she's more vulnerable now, more worried.

"The most important thing about Mary Beth is she's an orphan child. Her father walked out on her, her mother's dead. So she always feels like the outsider, and being a cop makes that worse; a cop doesn't belong anywhere. The orphan child is always apologetic in the face of authority. She wants to hide out. She wants to succeed by licking a thousand envelopes with no one looking. When Christine wears her long red cape onto the street, she wants to die.

"So she's this orphan kid that had the incredible luck of meeting a wonderful man when she was very young. her home is her religion. In the episode when she killed the kid, I wanted her to go to church, but the episode director (Georg Stanford Brown, who won an Emmy in 1986 for his work on "Cagney and Lacey") pointed out that she wouldn't go to a church, she'd go home, home is her church. Another time, when I wanted her to wear a gold cross, the director, Ted Post, said 'She doesn't wear her religion on her chest.'

"Mary Beth and Harve have a real love story. When they want to write problems, major problems, between them into the script, I say: forget it, this is a love story. I don't care if you don't know anybody like them, this is love. Harve is really her first priority. Before the kids. He rescued her from being an orphan.

"In a way, people thrust Mary Beth into a maternal role. Certainly she's that in the precinct. She doesn't always want that. As a matter of fact, she's less interested in the kids she encounters on her job than Christine, the childless woman. I sometimes think a childless woman can be more interested in other people's kids."

I ask how her experience of giving birth to Alyzandra influenced her portrayal of Mary Beth's giving birth. "It was very hard," she said. "I had to film the episodes of Mary Beth's late pregnancy and giving birth when I was nursing Xany. I had to nurse her over this belly pad they had on me to make me look nine months pregnant. I think they though I could use the experience of my own labor for Mary Beth, and usually I would. I have my own method. I draw on my own experiences. But on this one, I totally blocked out. I didn't want to use the experience of giving birth to Xany, which was very private-well, I just didn't want to use it. So my subconscious blocked; I could not call up any memories for it. I had to use other things. You know, being an actress means living someone else's life, and I didn't want to live someone else's life, have someone else's baby; I wanted my own."

I ask her about the problems of being a working mother, which are heightened by her being a celebrity as well. "Partly it's hard, but I'm from a theater family (her father, the late James Daly, was also an actor-as is her mother, Hope Newell) so I'm kind of used to it. Sometimes I guess the kids resent it. One time we were in a hotel in New York and there were al these paparazzi standing around flashing bulbs, and my kids ere upset. So I was real brave, see, I walked up to them, and I said, 'Listen, fellows. Give us a break. We're on vacation." They said, 'We're not interested in you, lady; Elizabeth Taylor's in the hotel. It was very humbling. Which his good because, let's face it, being an actor is a terrible act of hubris. I stand in the light and tell you a story while you sit in the dark and pay for it. Crazy."I ask her what actresses she admires. "I was formed by the stage, so what I like is the myth of actresses, dead actresses I never could have seen. Duse rather than Bernhardt. Bernhardt is about stardom, glamour, facility, great heart. Duse is about the insistence of individual interpretation, about conduct. I love all kinds of actresses-Fanny Brice I love. Katharine Cornell. I've thought of playing her. She got on trains, she took theater out to the people. I like that. I really admire Geraldine Page."

I ask her if she agrees with Gless about the decisions that go into playing with another strong women. "Sure," she says. "We have a lot of respect for each other. We make each other laugh."

And that, really, is what "Cagney and Lacey" is all about: two women who respect each other and make each other laugh, who weep together after the life-saving surgery of one, who argue abut procedure as one holds her went pantyhose out the car window while the other drives. "We're playing a romance, we're as romantic as anybody," Sharon Gless tells me. She's right. It's a romance whose celebration is love over due; the romance of women's friendship.

The Indomitable "Cagney and Lacey" (sidebar article)

When "Cagney and Lacey" executive producer Barney Rosenzweig accepted the 1986 Emmy for best drama series last fall, it was a moment that had been a long time in the making. "Cagney and Lacey" had begun its video life in 1981 as a television movie, conceived by writers Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday, starring Tyne Daly and Loretta Swit, and auspiciously launched by a Ms. cover story (October, 1981).The TV movie garnered a phenomenal 42 share in the ratings. (A 25 share is considered the hit level for a made-for-television movie).

Six months later, in a mid-season replacement slot, "Cagney and Lacey" debuted as a series starring Daly and Meg Foster. It was canceled after three episodes, but the tenacious Rosenzweig persuaded CBS to air the other completed episodes during no-lose, ratings-dead period. Buttressed by a publicity tour, these "Cagney and Lacey" episodes got ratings good enough for the series to secure a place on the fall, 1982 schedule, and Meg Foster was replaced by Sharon Gless.

However, in the fall of 1983, when Tyne Daly collected the first of three Emmys as best actress in a drama series for her portrayal of Mary Beth Lacey, "Cagney and Lacey" had been canceled again. But the series had another ratings surge that summer in reruns. That, plus the wide and favorable comment from media critics prompted by Daly's Emmy, and the letters of a loyal and outraged audience (with whom Rosenzweig kept in touch after storing the names of fans in a computer bank) brought the show back on the air in March, 1984. This time it stuck.

Now well into its fifth season, "Cagney and Lacey" has become a byword in quality television and various women on its writing and production team are already launching new projects. "L.A. Law" was cocreated by former "Cagney and Lacey" producer/writer Terry Lousie Fisher; director Karen Arthus also directs network miniseries; and "Cagney and Lacey" cocreator Barbara Corday heads Columbia Pictures Television.

The Emmy "Cagney and Lacey" won in 1986 was its second consecutive best drama series award from the television academy, and it joined a trophy case full of other awards and citations the show has received especially in the last two years. For the first time in four years, however, Tyne Daly did not receive the best actress Emmy, but Sharon Gless (who had been nominated but lost out to Daly three times before) did-finally and deservedly getting her own recognition.

Back to start of Cagney and Lacey section

My Index Page

|