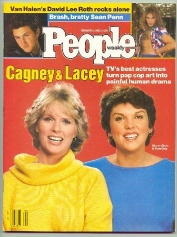

People, Feb. 11, 1985

A Method in the Madness: Cagney & Lacey grapples with cancer in a

grueling, rewarding episode

The CBS television series Cagney & Lacey is famous for taking risks.

Its subject matter, the working relationship between two women in the

New York Police Department, is unique on network TV, and its position

near the top of the Nielsen ratings disproves the theory that feminist

subject matter alienates male viewers. The series has been canceled

twice and brought back by viewer demand; not it has a weekly audience of

24 million viewers, almost half of them male. Beginning next week Cagney

& Lacey will air a two-part episode that promises to be one of the most

talked-about in the series' history. The subject is breast cancer. The

action unfolds after Mary Beth Lacey develops a lump in her breast and

attempts to deny what is happening to her. It is a difficult episode

that forces her friend Christine Cagney to play against type, to be

compassionate, caring and concerned, while the normally warm Lacey

becomes confused, angry and anguished. Filming this episode placed

enormous strain on both actresses. This is an account of how it

happened.

Shatto Street, in the mid-Wilshire district of Los Angeles, looks as

much like New York as George Hamilton resembles Ed Koch. Its grungy

apartment buildings, low slung to comply with the earthquake code, are

separated by alleyways wide enough for a Manhattan developer to build

towers of luxury condos. The New York license plates on the cars and

taxis parked along the block are a vibrant yellow-much brighter than the

dirty mustard of the real thing. Sharon Gless, 41, an ebullient,

irreverent woman for whom the role of the driven Christine Cagney is a

considerable piece of acting, is standing in a parking lot, smoking one

twentieth of her daily ration of cigarettes and joining in vigorous

laughter at an inside joke told by one of the production staff. Tyne

Daily, 38, for whom the role of the high-strung,

motor-mouthed-but-motherly Mary Beth Lacey is a less striking transition

from her off screen nature, is sitting on the stoop of a tumbledown

building, using the mental tricks of a method actress to preserve her

performance mood while the background action of the next scene is

rehearsed. In her hands are knitting needles and skeins of eye-popping

fluorescent yarn. She is knitting as if she were a character in an

Ingmar Bergman fantasy, one who can save her soul from the Devil only if

she finishes a muffler in 15 minutes. "I'm a little preoccupied right

now," she says, scarcely looking up from her handiwork to acknowledge

her visitor.

Just about every television viewer in America knows that Christine

Cagney is ambitious, competitive, sometimes cruel and often humorless.

She also possesses a keen psychological awareness that reality as it is

understood is different from reality as it is really happening. Thus,

between takes, Detective Cagney, in her tight jeans, shearling coat,

gold shield and Police Special, approaches the visitor and announces, in

a voice that carries smoke marks as pronounced as the ballistics grooves

on a spent bullet: "Let's get the easy stuff over right now. I sleep in

the nude." The hard-driving Cagney then dissolves into vivacious Sharon

Gless, a comic so incorrigible that a dozen years of convent schools and

two years of a Jesuit university (Gonzaga, in Spokane, where her

academic career was shortened with a suspension for smuggling beer into

a dormitory) failed to make her solemn. For the next three days,

whenever Gless encounters the visitor, she repeats in stage whisper, "I

still sleep in the nude."

Mary Beth Lacey transmits the pain through her face, her eyes, her

walk, her voice, every patch of her body except, perhaps, her hair. For

a week now she has known she has cancer, and the awful truth has

redefined her life. It has likewise possessed and remade the life of

Tyne Daily, the woman whose body she shares At the C and Lacey studios

in East Los Angeles, Mary Beth has just finished taping a scene in which

she tries to submerge her anxiety about the lump in her breast while

counseling a woman whose 8-year-old son has become involved with drug

dealers. It is Mary Beth, not Tyne Daily, who makes her way back to the

star's trailer during a break in the taping.

"We're supposed to talk at lunch, aren't we?" she asks, her usually

strong voice overlaid with an unaccustomed crackle of anxiety. "God,

there couldn't be a worse day." She moves a few steps farther, and a

woman from the production staff wraps her in a heavy, heartfelt hug.

"She really needed that," the aid says after Daily moves on.

The boredom inherent in any filming of a television program stalks

this episode of C and Lacey. In the best of times, there are endless

takes and retakes. This episode is directed by Ray Danton, a brooding,

sallow man known in the trade as "Midnight Ray," partly because of the

long hours he demands, partly because his temperament on the set seems

to resemble the color of the sky in dead of night. Danton is largely on

good behavior in this episode-charming, rarely moved to ire, often

avuncular with his actors. Still, filming one courtroom scene takes the

best part of a day, with endless breaks to change camera positions. One

take needs to be redone because Danton notices that Christine Cagney's

watch has run almost an hour ahead of its position from the last scene.

"As Stanislavsky said, "he bellows in a guttural Russian accent, "Kak

pozhivayete!-God is in the details." He uses the phrase at least a dozen

times a week, proving that the people on the set are either unversed in

Russian or in unusually generous spirits. Kak pozhivayete means,

roughly, "How 'ya doing?"

The struggle for perfection begins to take its toll on the staff; a

group of gaffers forms a conga line, scratching each other's backs and

snaking through the set during what must be the thousandth lighting

adjustment. When the temperature reaches what passes for arctic in Los

Angeles-about 55 degrees F-a technician announces that he is cold,

inadvertently producing the day's best dialogue with Mo, the venerable

sound man:

Techie: I wish I had long underwear.

Mo: I lent my long underwear to an actor. Remember Evertee Sloan?

Techie: Yeah. Whatever happened to him?

Mo: He died.

Techie: Did he have your long underwear on?

Mo:I don't know. But I never got it back.

By day's end, the boredom is brain numbing. Everyone in the room has

heard the scene two dozen times the actors are having trouble keeping

their performances sharp, a notably irreverent lighting man is actually

reading a prop Bible, and a hairdresser, given to wearing gold baubles

and bracelets along with his Parachute outfit, is reading the football

stories in the morning sports section.

The newspapers in Los Angeles have been filled with reports of a

scientist who theorizes that the human pineal gland, a much maligned

organ, actually has a function: It reacts to the stimulus of light to

produce mood elevation. Take away light, as in winter in northern

climates, and you produce depression. Restore it, and you make people

cheerful. Sharon Gless, who has spent almost all of her life in Southern

California, could well be used to prove this theory. Her cheerfulness,

even in discussing personal topics, is Olympian. "I have these

adolescent fantasies that have never been fulfilled," she ventures. "I

was raised on all those Rock Hudson, Doris Day films; Walt Disney ruined

my life. I keep waiting for my prince to come off the screen and just

sweep me away. There are times when I think, gosh, this is the time,

this is the one, but I never get married, so metaphysically speaking I

must be very happy. Where do you want to be? Look at your feet. I guess

I want to be right here, so I must be happy being here. There are times

when it's good being without a beau. I keep changing, and the changes

have been so rapid in the past few years that sometimes I'm afraid I'm

going to wake up and not care for the person I went to bed with the

night before." A former boyfriend once threatened to throw a shower for

Gless, with a printed invitation that would read, "I'm not going to

marry the girl, but that's no reason she shouldn't have nice things."

Gless has a constant companion, whom she calls her beau ("It's a lot

better than 'main squeeze'"). She says, "Time is running out, so I guess

the children thing isn't in the cards. Marriage may be in the cards one

day." For now she has gone out and bought herself a set of Baccarat

crystal, which lodges unopened in the small, secluded San Fernando

cottage she calls home. "I just wanted the goddamn crystal. It was one

of those adolescent fantasies," she explains. "I don't use it; I don't

even have a dining room. I guess it shows you what I think of myself

that I'm not worth opening the Baccarat crystal for," she adds,

laughing. "That will be my next period of growth, when I open the

Baccarat crystal just for me."

Visiting Tyne Daly in her trailer is like entering a sickroom. For a

week she has been living with the certainty of impending doom. "Tyne is

a very intellectual actress," says Barney Rosenzweig, the executive

producer. As a method actor, she internalizes the problems and attitudes

of her role, and hangs on to them with a terrier's tenaciousness, making

them her own for as long as she needs them." Before this episode

started," Sharon Gless says, "Tyne came to me and said, 'Now listen,

however I treat you, don't take it personally. I have cancer.' She feels

that she is living with this disease. Because we know her and we love

her, we're gentle right now. She's quite fragile." Nothing in the week's

events contradicts that assessment. Just that morning she had seemed on

the verge of emotional fracture. It is strangely disconcerting when she

greets her visitor like the cheerful chatelaine of a mobile home,

introducing her daughters, Kathryne, 13, and Elizabeth, 15; and hefting

a bottle of a first-rate Sonoma Valley Chardonnay. She pours a liberal

glass with the invitation, "Go ahead, have some. It's Christmas wine

from what's -his-face." His face-let alone his name-is never established

as she launches into a half hour of cheerful badiage, earnest self-

explanation, the sort of manic Celtic fatalism that is impossible to

describe but, as with pornography, you know it when you see it.

"Some pieces are easier than others," she begins. She is using the

voice of Tyne Daly, refined, articulate. She is a child of Suffern, N.Y.

of prep schools and of the man who is referred to in press releases so

often as "the late actor James Daly" that you think the poor fellow

never showed up on time in his life. Within seconds Tyne is lapsing into

Mary Beth's voice. "In this one, ya've got ta go to funny places. Death

and illness places. (Long, world-weary intake of breath.) Whadeva. This

one is very distracting, very preoccupying. At this stage of the game,

this character talks to me in the middle of the night. She tells me

stuff."

A tape player in the rear of the trailer is playing the music of the

Beatles' greatest period: Norwegian Wood, Nowhere Man, Yesterday.

Nothing is to be read into this, Daly insists. "My daughter Kathryne is

reintroducing me to the Beatles," she explains, as the 13-year-old, a

model of that teenage mix of grace and gawk and curiosity, remains

mute-reclining on the closed commode of the trailer. There is, in fact,

almost no nostalgia in this woman, product of the '60s, in and out of

Brandeis in a year, before the Vietnam unpleasantness, graduate of the

American Musical and Dramatic Academy in New York, where she met and

married her husband, Georg Stanford Brown. Instead, she sees life and

her work in tough, hard terms to which romanticism is admitted only as a

visitor.

"Look," she says, "we're having lunch here, and I have to go in 10

minutes and pretend to have cancer and pretend to be facing a very

difficult decision on whether to go and face the music and see a doctor

or not. I also have to sit here and have this tuna fish sandwich. I also

have to say to my children hello. I have to say to you some words. I

have to have already made a real tough plan for what I'm going to do

before the camera and know all about the timing and the feeling and the

character's intentions so I don't blow my wad. I can't just be stupid.

I can't just want to show myself off, or my body, or my face. I have to

reveal something for an audience that doesn't have to pay attention to

me if it doesn't want to. And that's the discipline part-nobody cares.

It doesn't matter to the people who watch it what I went through, how

much I suffered, how much I sweated, how many tears I shed, how many

sleepless nights I spent trying to figure out how to do it. It matters

what they saw-and, frankly, they'd rather hear about whether or not my

marriage is screwed up than hear about this."

There are few subjects Tyne Daly would like to discuss less than her

private life. She and Brown, 41, have remained happily married since

their student days. Although he once starred in The Rookies, he has

forsworn acting for a career as a director of such hit series as

Dynasty, Hill Street Blues, Miami Vice and even, occasionally, C and

Lacey They have made their lives private and apparently prospered. "It's

a working marriage," she allows. "A work in progress. You try every day.

Loving is as strict as acting. If you want to love somebody, stand there

and do it. If you don't, don't. There are no other choices."

In all of life's endeavors-acting and quarterbacking in football and

raising a family and doing neurosurgery-there are two kinds of

successful people. One kind, Sharon Gless' and Doug Fluties's kind,

makes success seem easy. The effort is hidden, only the success is

visible; the yards are gained in gigantic chunks, in a brilliant,

graceful, airborne game. The other kind, Tyne Daly's kind, is a game of

inches, where every gain is hard fought and hard won, and blood is

everywhere in evidence. "I had great objections to this part from the

beginning," Tyne Daly explains, then turns from the subject to assure

her now intensely bored teenager, "This is the best sandwich I ever had,

Kathryne. I just want you to know that." The daughter, despite herself,

grins. Back to the subject, Daly goes on: "I said to the writers,'****

it, guys, what's the matter, you don't like me? You want to give me

cancer? Poor old Mary Beth's had a hard goddamn year.' I took it

personally when they wanted to give me cancer. My first reaction was

rejection." But the real Tyne Daly, the woman for whom success is a

relentless ground game, soon asserted herself. "I realized that as long

as there are women being led astray by the medical establishment, women

getting hacked up into pieces, it's important that I tell the story, and

it's important that I face the music."

The subject matter of this episode, with its intricate plots and

subplots, is drugs, ghetto life, racism and cancer. Not just the script,

but the whole cast, could sink beneath the weight of these heavy topics.

One of the things that redeems the situation is Sharon Gless. "I am a

comedian by nature," she says, puffing on a cigarette just seconds after

delivering one of the most wrenching scenes Christine Cagney has ever

been forced to produce. It is a courtroom episode in which she begs a

judge to restore a child to a mother who lost custody on what was now

clearly an incorrect and racist recommendation made by Cagney. Gless'

interpretation of the role is on target. "Comedy comes much more easily

to me than draaaaamaa," she says, laughing, then dragging again on her

cigarette. "I like to just pull out my rubber chicken and throw it into

the air."

If you ask Sharon Gless how much of herself she puts into her

character, you begin to realize what a loss stand-up comedy suffered

when she want into series television. "There are some similarities

between me and Christine," she begins, sound a little practiced, like a

star recalling the standard interview. Then the zaniness begins to crawl

out of her pores. "There are differences, though. Christine is thinner.

I could never get into her jeans. I think that Sharon is funnier than

Christine. But that fact is that Sharon is single and driven. I love my

work, Christine loves her work. We're both blondes," (Perfect four-beat

pause as she gestures toward her frosted once-brown hair).

"Weeeeelllll...Christine's a blonde."

The production is back at the studio, the mood somber after two

weeks of cancer. The entire cast, the regular extras, virtually anyone

with even a tenuous connection to the show is on the set, because this

is the day of the annual backstage C and Lacey's Christmas party-a

one-hour recess of happiness and joy in a day of fictive misery. The

squad room players have taken their regular places for a climactic

scene, in which Mary Beth will announce to her police colleagues the

nature of her disease. The transference of character from Tyne Daly to

Mary Beth Lacey is complete: Though her fellow actors associate with her

and offer their support, the crew is giving her the wide berth reserved

for the terminally ill. "Have you found it yet?" she demands of the

visitor to the set, who is searching for a half-remembered line from

Yeats. Yes, he has. It's from The Circus Animals' Desertion, with its

definition of acting: character isolated by a deed to engross the

present and dominate memory, but there is no time to read it to her. The

bell rings, and her scene begins.

Al Waxman, earnest as ever, becomes Lieutenant Samuels and

approaches Lacey:

"..you should, uh, consider taking...time off..."

She answers:

"I explained to you that won't be necessary, Lieutenant..."

"Lacey..

"Sir, if that's all, I gotta lotta stuff to do..."

Up to this point, the 30 or so cast members are paying good,

union-scale attention. doing their jobs as actors and extras. But now

Mary Beth or Tyne, whoever the woman is, reaches down and finds a

two-foot stack of folders on her desk chair. She raises them in a single

round movement, and thunders:

"What is this, the city dump? Who put these here?"

Samuels tries to help her with the files; she flings them in a

gesture of manic strength, and they skid to a stop under Detective

Isbecki's feet. There is anger in her manner, passion in voice, and

suddenly, even the grips are stunned as she utters her next lines:

"I have cancer. I have breast cancer...It's this one here, the left

one...(She rips off her jacket, casts it to the floor and jabs at her

left breast with her right index finger) Does that satisfy everybody's

curiosity? I have to have an operation-but I do not want people treating

me like some kinda freak! I'd appreciate it if everybody here would

please...forget about it..."

It is Mary Beth's Lacey coming out of Tyne Daly's "strange death and

sickness places," a diapason swell that fills the set and leeches into

the crevices of her auditors' beings. The stage directions call for "a

painful beat of silence...then Lacey picks up the files and exists

toward the file area."

But instead there are five or six beats of silence. Then a few of

the actors nearest to Daly begin to applaud, then all of the cast, then

all of the extras, then the staff, everybody. "Best ****acting on

television," says Ray Danton. And nobody in this room, transfixed and

teary eyed and overjoyed that Mary Beth has finally decided to deal with

her problem, would ever disagree with him."

Back to start of Cagney and Lacey section

My Index Page

|