In Defense of Internment

This is a book which is in favor of the internment of persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II, and is written by Michelle Malkin, who is a strong conservative.

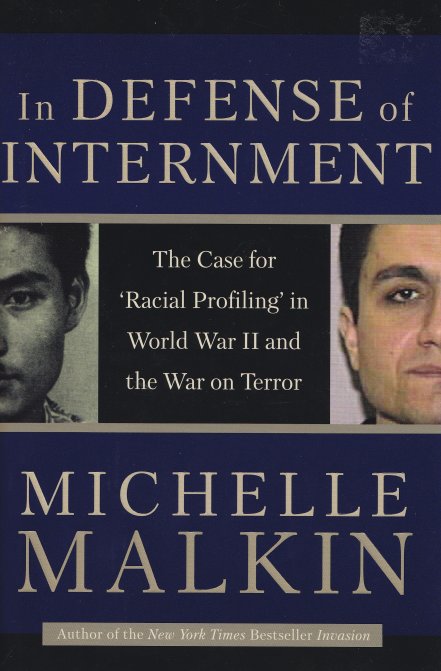

The book is subtitled The Case for 'Racial Profiling in World War II and the War on Terror. The cover shows what type of book it is, since there is a picture of a modern-day terrorist linked to a picture of a person of Japanese ancestry for the time of WWII.

The book is not as badly written as other books on this same topic. She presents her arguments in a fairly straight forward, usually non-wild manner. Her problem is that she doesn't consider the culture of that time, and she has some logical errors big enough to fly a B-29 through.

First, one would get the impression that the book, from the cover, spends lot of time on the current War on Terror, and makes a strong effort to link that back to the internment process. Actually, that's not the case at all. The vast majority of the book is on the internment, and only a small bit is on the War on Terror, and links between the two are quite weak.

“Ethnic Japanese forced to leave the West Coast of the United States and relocate outside of prescribed military zones after the Pearl Harbor attack endured a heavy burden, but they were not the only ones who suffered and sacrificed.”

Quite true, but she overlooks a major point. Yes, almost everyone suffered and sacrificed in World War II, but that was done voluntarily (except for those who were drafted into the military). People lived with rationing, cut back on purchases, saved scrap metal and paper, etc, but all this was done with their compliance. The persons of Japanese ancestry, on the other hand, were forced to leave their homes and businesses without any concern for their civil rights. They were not charged with any crimes. They were not arrested and put on trial. They were rounded up based on their ethnicity, forced to leave their homes and businesses (often suffering financial ruin as a result), then shipped off to various camps, forced to remain there or, if allowed out, were allowed out only on certain conditions.

This was enforced suffering, not voluntary, and, as such, was much worse that that of other person in the war (with the exception of those who lost loved ones.)

Later, she says people don't remember or understand the conditions that existed at that time, and I fully agree with her. Japan had attacked the U.S. Their armies were marching through Southeast Asia. There were some sinkings of merchant ships by Japanese submarines, and there was even very limited shelling of the U.S. coast by Japanese subs, and a couple of incidents where a Japanese sub-carried plane tried to start forest fires (during the wet season.)

What she totally fails to go into is the pre-existing prejudice against Orientals on the West Coast of the U.S. (I have reviewed a number of books on this topic and there are in my reviews section, along with related samples in my newspapers section.) The movement of PJAs (Persons of Japanese Ancestry) out of the West Coast area was as much a matter of ethnic prejudice and economic jealousy as it was anything else, if not more so.

She spends a chapter on one incident where a Japanese flyer was aided by PJAs after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was eventually killed by someone on the island. There was also one instance (which she doesn't recount) of a couple of PJA women helping Germans who had escaped from a P.O.W. Camp. Outside of those two examples, that was pretty much the extent of regular PJAs betraying the U.S.

Now, there were PJAs working in Japanese consulates, and she spends a lot of time on that subject. Those people would be expected, naturally, to work for the Japanese government and not care about the U.S. They were not reflective of the “average” PJA in the states at all.

“After December 7, 1941, it would have been unforgivably irresponsible of American officials to ignore the possibility of attacks on the mainland-...”

She is, of course, totally correct on this. What she doesn't really consider, and herein is her biggest error in logic, is that, if the U.S. West Coast was in danger from Japan, then Hawaii was REALLY in danger from Japan. It is a lot closer to Japan than is the U.S. mainland. It had already been attacked once (and was, in fact, bombed again, but on a much more minor scale.) If the Japanese were to attack, then Hawaii, not the West Coast, would have been the logical place for an invasion.

What one has to consider, again, is the difference in the times. In today's world, attacking the U.S. from Japan would be comparatively easy. ICBMs could reach the US. There are planes that can fly the distance without refueling, and ships that can go the distance without refueling.

Back then, there were no such missiles, and there were no such long-range planes or ships. Refueling and reprovisioning were major problems for both sides during the war. At attack on the U.S. West Coast would have stretched Japanese resources far beyond what they could actually manage. Remember, Japan was already in China. It was moving through Southeast Asia. It had attacked Hawaii and the Aleutian Islands (which she also doesn't remember to include.)

Their forces were stretched as is, and to attack Hawaii would have been very difficult, but not totally impossible, but attacking the U. S. West Coast in strength, rather than by a few very isolated submarine incidents, was pretty much out of the question.

Also, consider that about 1/3 of the people in Hawaii were PJAs. (A much larger percentage than PJAs on the West Coast). Since there were many more PJAs in Hawaii proportionally, and since Hawaii was within striking distance for a major invasion (albeit pretty much at the limits of their abilities), then why weren't Hawaiian PJAs gotten off the island and shipped to the mainland. Logically, if Malkin's suspicious about PJAs are accurate, then the PJAs on Hawaii posed a much more dire threat to U.S. security than did those on the West Coast.

Yet, there was no major movement of PJAs off Hawaii. Some were arrested and removed, true, but this was a very small percentage of the overall PJA population. Why weren't they moved? Because they were a major part of the work force, and removing them would have severely damaged the economic structure of Hawaii (not counting the fact that it would have tied up numerous boats that would have been used for shipping PJAs from Hawaii to the U.S., rather than using those boats directly for the war effort.) So, the PJAs stayed in Hawaii (under wartime conditions and controls, of course.)

So, if her fear of PJAs was actually justified, then the ones in Hawaii should have been moved first and foremost, and the ones on the mainland secondly, yet only the ones on the mainland suffered a major resettlement, and then only those PJAs on the West Coast.

Again, logic is a problem for her. If the PJAs were so dangerous, subversive and willing to cooperate with the Japanese military, then it would be logical to gather up ALL the PJAs in the entire country, not just in one part of it. What logic holds for some must hold true for all, or for none at all.

Also, a lot of her examples of subversion, etc, take place in other countries, primarily in Southeast Asia, and not in the U.S. These were countries being invaded actively by Japan and, as in any war, some people will try to curry favor with the enemy.

She spends a lot of time going into the various Japanese organizations in the U.S., including the Japanese language schools. There were, indeed, such organizations. What she doesn't adequately point out is that the organizations were already under scrutiny, and, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI picked up most of the leaders of these organizations within a day or two (whether or not they were engaged in anti-U.S Activities.)

She spends a lot of time on the MAGIC intercepts. She says, for example, “...a series of MAGIC messages revealed Japan's intent to establish an espionage network in the United States.” Well, duh. Of course they would. Again, what she doesn't point out is that these were run through the consulates, and the Japanese agents weren't really able to get many volunteers among the PJAs in the U.S.

She spends some time over the fear of radios in the hands of PJAs. Well, for one thing, many of the PJAs were fisherman, and having radios was not unusual. Actually, anyone having radios was not unusual, since this was before television, and radios, shortwave and otherwise, were about the only way to keep up on world events. Having a radio was not a sign of some evil, devious purpose at work; it was a sign of a regular person having a regular interest.

She talks about the lack of internment of Italians and Germans in the country, and says “...there was no evidence that Germany or Italy had organized a large-scale espionage network...” This sort of overlooks the BUND, which was a fairly major organization in the Eastern part of the U.S.

Like other books in the series, she tries to paint a fairly rosy picture of conditions in the internment camps, totally overlooking the fact that the people were forced to go there without any attention being paid to their legal rights. Anyone who goes over my reviews of books on the camps will see that conditions in those camps were anything but rosy.

She writes about violence at some of the centers, and that is correct. There was violence in some, and deaths in some. A good part of this was brought about by the loyalty test given to the PJAs, and the tremendous split in the PJA community over what questions 27 and 28 meant, and how they should react to them. Also, she doesn't factor in the fact that these people were put into the camps and kept there against their will (until programs were set up for allowing some to work outside of the camps.) It's perfectly natural that some violence would eventually erupt, given the conditions the people lived under.

It's also amazing how far some conservatives will go to justify their beliefs. She writes “There is not one documented case of an ethnic Japanese espionage agent or saboteur-Issei or Nisei-turning himself in to U.S. authorities.” A shocking condemnation of PJAS?

No. Just a matter of logic. If you were a spy or a saboteur would you turn yourself in to the authorities? I don't think so.

The basic information part of the book is 165 pages long. Then, there are 144 more pages of documents and photos, allegedly to prove her points.

A lot of them are very standard things, things that one would expect be sent from a consulate to the home country. There are also some rather interesting things included.

In a paper from March 12, 1941, Hoover, head of the FBI, says that the Japanese espionage effort is going to be moved to Mexico. So, it if was going to Mexico, why ship out the U.S. PJAs to the camps?

A paper from the Navy Department, dated December 4, 1941, talks about PJAs in Hawaii, and how almost all of them “belongs to one or more purely Japanese organizations.” By Malkin's logic, then these people were very, very suspicious and should have been moved to the mainland camps, but they weren't.

A paper from January 26, 1962 notes that “..the entire 'Japanese Problem' has been magnified out of its true proportion...and, finally, that it should be handled on the basis of the individual, regardless of citizenship, and not on a racial basis.”

In other words, no mass evacuation was called for.

A number of the papers she includes have nothing at all to do with PJAs in the U.S. or Hawaii of the time. They deal with Mexico, Latin America, and other areas of the world.

She has some photos, noting in one of them a PJA named Richard M. Kotoshirodo, and that he was involved in gathering intelligence. She doesn't point out that he was working for the Japanese consulate at the time.

Thus, what we have is a rather flawed book. It doesn't examine the history of the times very well at all. It includes material that is totally irrelevant to the book's major thesis about how untrustworthy PJAs on the mainland were. It has major logic flaws. It's a typical conservative argument based on half-truths, omissions, and diversions. It might seem sort of convincing to someone who had read only this book and nothing else on the internment process, but to any person aspiring to be a historian, the book shows its limitations all too easily.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|