These Are Americans: The Japanese Americans in Hawaii in World War II

John A. Rademaker, 1951.

This is a over-sized book with lots of photos of Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Japan, and a lot of good information, though, due to its age, it might be hard to find except in a library.

The book talks about the problem with the draft in relation to AJAs on the Pacific Coast of the US. They were detained in internment camps (with no charges against any of them), yet they were being asked to fight for the very government that was denying them their basic rights as Americans. (2/3rds were American citizens.)

”When the right and duty to serve in the armed forces was restored, but the right to freedom of person and property from illegal restraint and detention, the right to freedom of speech and movement, the right to economic activity unhampered by discriminatory separation from their property and unprotected pilferage of their property in their absence, and illegal confiscation of their goods, businesses, and lands by covetous neighbors, was not restored at the same time, they protested, as any democratically trained person would, against the injustice of being asked to bear the burdens of our defense, while being denied the benefits of the citizenship which was theirs, which no other citizens were asked to forego.”

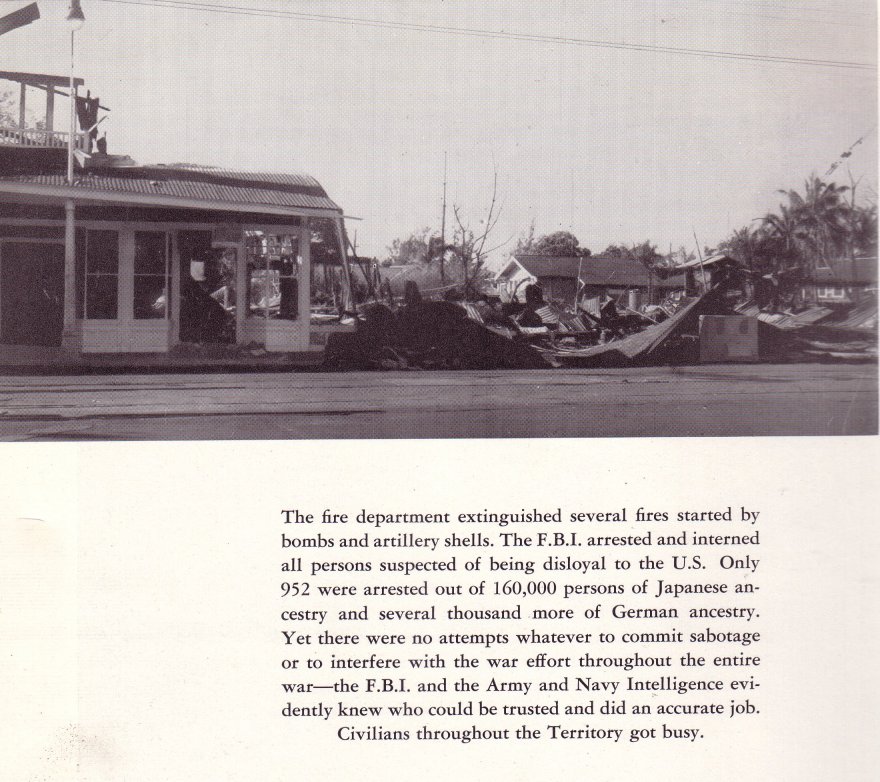

As of December 7, 1941, about one-third of the people living in Hawaii were of Japanese ancestry. “Yet not one case of fifth-column activity was attempted by anyone of Japanese ancestry except the specially imported agents of the Japanese consulate. ...The fact that none of the 150,000 attempted to help the enemies of our democracy, and that practically all of the able members of the 150,000 took active steps to help defend our 'rampart of the Pacific' shows clearly that whenever fascism or militarism meet the sincere convictions of a people who enjoy a democratic way of life, they will meet determined opposition and a spirited, united defense.”

The book describes the Nisei as “well-saturated with American customs, ideas, and attitudes.”

”The older generation, or immigrants, are not and never were permitted to become citizens of the United States. ... That fact has made it difficult for many older generation Japanese Americans to become really Americanized.”

”Although the Japanese Americans were confident of their loyalty to America, the American military and naval authorities were in no position to take for granted their loyalty in a period of crisis, in view of their responsibility for the safety of America's chief defense outpost on the West.”

A series of surveys were taken to attempt to determine the loyalty of AJAs (Americans of Japanese Ancestry) in Hawaii. “...it became increasingly apparent that there was no reason to question the loyalty of the citizens of Japanese ancestry, except for a small number of Kibeis who constituted one-third of one percent of the citizen population.”

Kibei were AJA who had spent at least some time in Japan, usually in schools, and then returned to the US or Hawaii. Their views on Japan were considered more suspicious than those of Nisei, who had never been in Japan longer than for a brief visit, if even that much.

From December 7, 1941 till the end of the war, some 1,440 AJAs were picked up by the authorities. This constituted nine-tenths of one percent of the AJAs in Hawaii. 879 of those were Japanese Issei, first-generation immigrants. 534 were Nisei.

Of the Issei, 301 were released after a hearing before an internee hearing board. Of the Nisei, 160 were released after their hearing.

This does not mean that the ones who were not released for guilty of anything, though. They were still held since they were leaders of the community, language school teachers, priests, etc.

”...no sabotage or fifth-column activities were committed or even attempted by persons of Japanese ancestry at the time of the attack on pearl Harbor, or at any other time. ... The Army authorities, the FBI, and the Naval Intelligence Office all agreed that the Japanese Americans would be dependable and would give no trouble, and events proved that they were right.”

The book provides some statistics on people drafted in Hawaii. 701 were inducted for the first draft call, and 419 of those were AJAs. They made up 59% of those inducted, even though they constituted only 34% of the overall population of Hawaii.

”There was no need for the wholesale evacuation of the Japanese American population. The arrest of the few who were suspected of being pro-Japan was ample safeguard for the safety of the Islands, as events proved conclusively.”

From April, 1942 to April, 1944, registrants of Japanese ancestry were not accepted in the armed forces by being drafted, but only by volunteering.

Over 13,000 AJAs from Hawaii served in the armed forces by the end of the war, 4000 of those being volunteers. Many others actually volunteered (over 6000) but were not accepted for physical or other reasons.

”...the Japanese Americans...are determined to make their homes here, to live under the United States government, and to bring up their children, and themselves to be, in every sense of the word, loyal Americans all.”

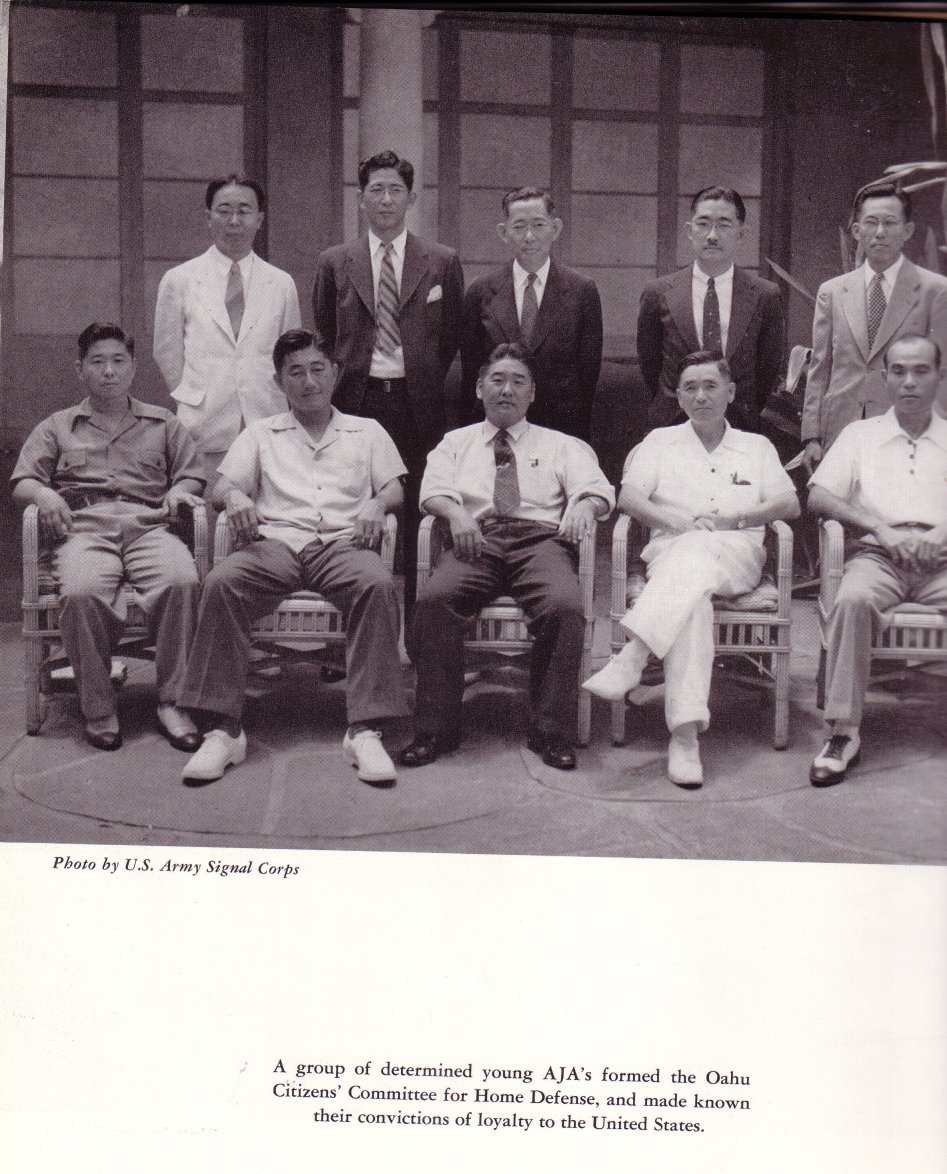

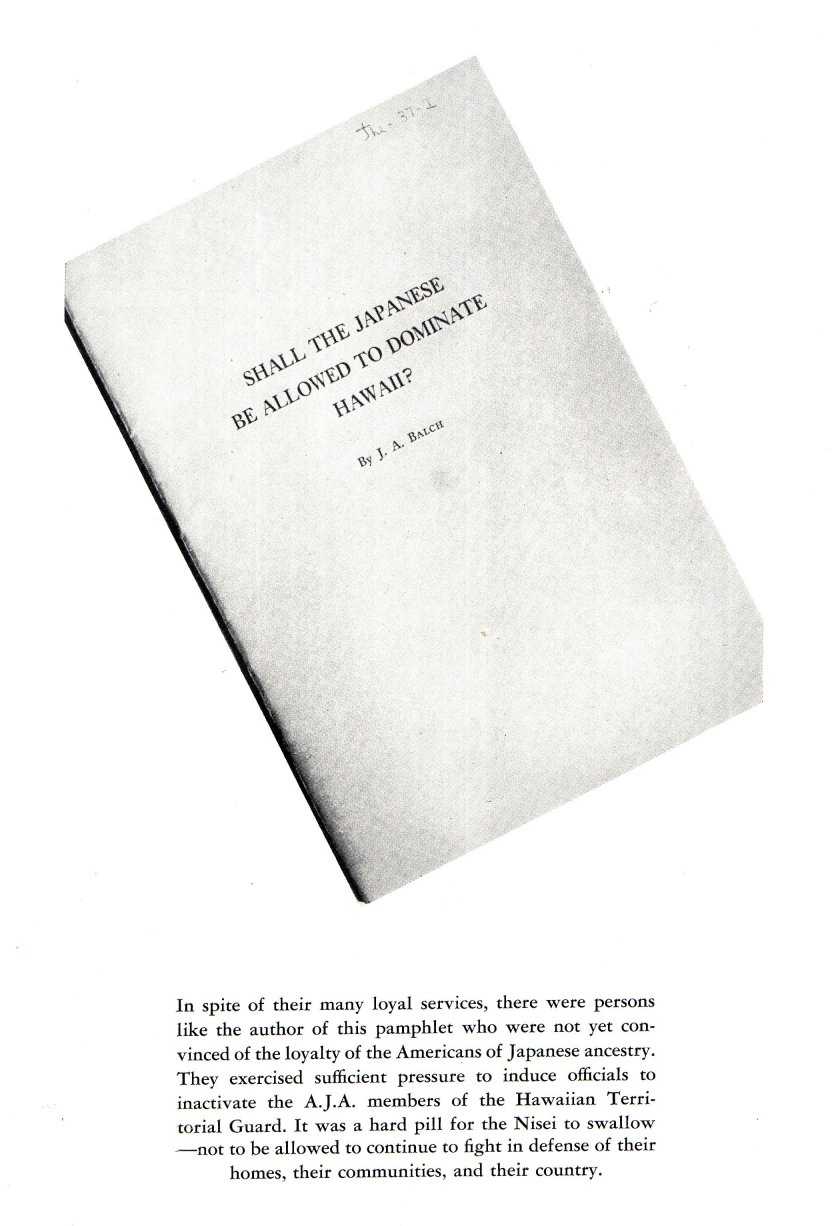

There's a very interesting section talking about how the attitude towards AJAs changed in Hawaii somewhat. Apparently as more people in influential positions and military men unfamiliar with the nature of the AJAs in Hawaii entered Hawaii, they brought with them their anti-Japanese biases. This led to the decision “...in spite of their loyalty and their hard, conscientious work during the days in which the danger was real and when people were dying rather than retreating to positions of safety” to remove AJAs from active participation in combatant military duties. In other words, guns were taken away from them, for example. A construction group did major work, but under the guns of US soldiers. Things like that.

One example were the men in the Hawaiian Territorial Guard that were of Japanese descent. (The group was somewhat like the National Guard in nature and purpose.) On January 19, 1942, all the AJAs in the group were told that they could no longer be used and were given honorable discharges.

Although there were spies, etc, in the Consular Office, “...there is no evidence that any of the local residents of Japanese ancestry...ever lifted a finger against the government of the United States.”

Apparently, most of the civilians killed or injured in the bombing of Pearl Harbor and adjacent areas were people of Japanese ancestry.

The book cites some of the rumors going around just after Pearl Harbor.

1. Two regiments of Japanese troops had been dropped by air near the University of Hawaii. The university's ROTC was sent to intercept them, and most of the members of that group were Japanese Americans.

2. Arrows had been cut in cane feeds by the Japanese population to direct the planes towards Pearl Harbor.

3. A transmitter had been found for sending messages to the attackers.

4. The sides of a milk truck in Schofield Barracks collapsed and Japanese with machine guns hidden in the truck opened fire on the soldiers.

All the rumors, of course, were totally untrue. The problem was that the people in Hawaii realized the rumors were not true, but the people on the mainland believed in the rumors since they were already quite anti-Japanese in their attitudes.

Apparently a movie was made about the attack. The movie was called Air Force and contained lots of the rumor-type things which helped even more convince the people on the mainland that AJAs were not to be trusted. When the film was scheduled to be shown in Hawaii, though, local authorities demanded that the “scenes drawn wholly from disordered imaginations and excited but unfulfilled expectations” be removed from the movie before it could be shown.

Another difference between Hawaii and the mainland was that authorities on the mainland did not try to deny or disprove the rumors such as in the film and the newspapers, while those in Hawaii actively worked to debunk them.

On the mainland “...it became highly fashionable politically to criticise them [AJAs] and to say they could not possibly be trusted with freedom to come and go on their regular business. In Hawaii, the rumors were taken care of promptly so that such hysteria could not arise or be fanned into an attitude so strong as to force mass evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the Islands.”

”...loyalty, and devotion to one's country are not based upon one's race, parentage, or ancestry, but upon education and the ideals one learns in the school, in the neighborhood, in the church, and in the community, from personal contacts, from books and newspapers, from the radio, and from the movies.”

On June 5, 1942, the Hawaii Provisional Battalion was organized and a week later was renamed the 100th Infantry Battalion, Separate.

There was a question as to whether to keep the AJAs together in the military, or to just place them at random in other groups. “...the War Department felt that by keeping them together, where the spotlight could be kept upon them, the Americans of Japanese ancestry could demonstrate to all Americans, ast home as well in the services, just what stuff they were made of, and whre their loyalties lay.”

”How do we know that Japanese Americans love the United States and the American way of life? We know because so many of them volunteered for combat service, when they might far more safely have shrugged their shoulders and accepted the opportunity to stay far away from the battle zone.”

Major General C.A. Willoughby: “In spite of the 2,000 to 3,000 Nisei used-40 percent of who were Hawaii-born-there has not been a single case of disloyalty or ill fielding. They did their job quietly and with great efficiency.” This referred to the Nisei used in the Pacific theater as translators.

The Nisei also worked on the translation of the documents of surrender of the Japanese government, and documents for commanders of various Japanese garrisons for their surrender.

The book also talks about the 1399th Engineer Construction battalion which was composed of AJAs.

A breakdown of what happened to the 100th Battalion and 442nd Combat team:

Killed in action – 569.

Died of wounds – 81.

Missing in action – 67.

Wounded in action – 3,506.

Injured in action – 177.

Total casualties – 4,120.

The 100th Battalion and the 442nd Combat Team won the following decorations:

1 Medal of Honor.

1 Medal of Honor

47 Distinguished Service Cross

1 Distinguished Service Medal

12 Oak Leaf Cluster to Silver Star

350 Silver Star

18 Legion of Merit

16 Soldier's Medal

41 Oak Leaf Cluster-to Bronze Star Medal

823 Bronze Star Medal

1 Air Medal

500 Oak Leaf Cluster to Purple Heart Medal

3600 Purple Heart Medal

2 Army Commendation Ribbon

40 Army Commendation

87 Division Commendation

1 brigade Commendation

12 Croix De Guerre (French)

2 Palm to Croix De Guerre (French)

2 Croce Al Merito Di Guerra (Italilan>

2 Medaglia De Bronzo Al Valor Militare (Italian)

There was also a women's group called the Women's War Service Association that was involved in helping wounded soldiers in hospital and writing letters to families which had lost a member killed in action.

The book has two main strengths. First is the amazing assortment of photographs, very few of which I have ever seen anywhere else. Second, the information content is very detailed and interesting and again generally does not cover what is found in other materials. Although a very interesting and useful book.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|