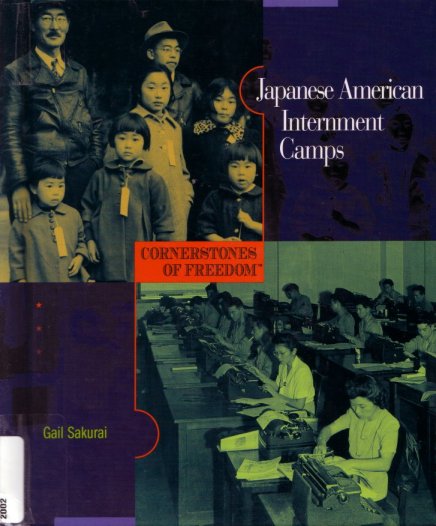

Japanese American Internment Camps

2002, Gail Sakurai.

(Note: My review is written as normal, but comments in [ ] are my own and are not taken from the book.)

The book points out that there were 160,000 Japanese Americans living in Hawaii and another 125,000 living in the U.S., mostly on the west coast. Two-thirds of those were actually American citizens. The book points out that hysteria caused many Americans to hate anything Japanese.

The book notes that, as to Hawaii, there was actually no long-standing prejudice towards the Japanese. On the mainland U.S., though, there had been such prejudice for decades. The same reasons given today for fearing immigrants coming into the U.S. were given then; that they would take jobs away from native-born Americans and that they looked different, their customs were different and their religion was different.

The Supreme Court rules in 1922 that Asian immigrants could not become U.S. citizens; a year later non-citizens were forbidden from owning land and one year after that Congress stopped all Japanese immigration.

The sign above is one telling Japanese men that they were to sign up for relocation. Relocation was voluntary at first, then mandatory.

Within the next few weeks thousands of Japanese, both on Hawaii and mainland U.S., were arrested and jailed but without charges or trials. They were men who were involved in business, journalists, teachers and fishermen. Many of them were held in prison camps until the war was actually over, totally denied their rights as U.S. citizens.

The book points out one incredibly pertinent fact; that "Despite these suspicions and accusations, there was never a single confirmed case of spying or treason by a Japanese American during World War II."

Not one.

It wasn't until March of 1942 that the military created "restricted military zones" in the U.S., including areas of California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona. [If the Japanese Americans were such a terrible threat, why did it take the military three months before they acted?]

Any Japanese Americans living in those areas were put under curfew, from 8 P.M. until 6 A.M. They had to turn over any weapons, cameras, radios and binoculars that they owned.

After the voluntary evacuations failed to remove all the Japanese Americans, mandatory evacuations were ordered. Each family was given a registration number which all the member had to wear. [Much like Jewish people in Nazi Germany had to wear yellow Star of David marks on their clothing]. The families were given a week to ten days to get all their affairs in order. This resulted in people selling their furniture and other goods, often at incredible losses. Things that were supposedly safely stored for them until their return were not safely stored at all; other people stole much of what the Japanese American families had owned.

There were 16 temporary assembly centers that they went to first since the "permanent" facilities were still being constructed. From those centers they were shipped to one of ten relocation centers. The book notes there were food shortages, and the camps were surrounded by barbed wire and had armed guards.

Conditions at the camps were not exactly great. Temperatures ranged from 125 degrees Fahrenheit at Gila River in Arizona to minus 30 degrees at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. The book also notes that George Takai, who became Mr. Sulu of Star Trek fame, was himself an internee when he was four years old, being interned at the Rohwer camp in Arkansas.

Not even the orphans were left out. In June of 1942, Japanese-American children from orphanages in Los Angeles and San Francisco were relocated to Manzanar in California. (109 children total.) [Exactly how much danger to the U.S. did these orphans pose? Relocating children with their family at least makes a little sense, but orphans? That's getting a little absurd.]

There is an excellent description in the book of the arrangement of the camps. There were structured in block arrangements. There were 14 military-style barracks in each section along with a mess hall, a laundry building and bathrooms. The barracks were 120 feet long, 20 feet wide and divided into six one-room apartments. They barracks were constructed of wooden boards covered with tarpaper. Each "apartment" had a wood-burning stove, one light bulb and a metal army cot for each person. Toilets were in communal areas as were the showers.

No Japanese language was allowed in the camps. Verbal and written communication had to be in English.

Something I had not read previously. Right after Pearl Harbor, 5,000 Japanese Americans serving in the U.S. military were discharged or transferred to non-combat units. In June of 1942, though, as an experiment the Army formed the 100th Infantry Battalion, an all-Japanese-American group that did so well Japanese Americans were once again allowed into the U.S. military, although such groups fought in Europe.

The book then makes reference to the loyalty questionnaire that caused so many problems for the internees with questions 27 and 28 being the problems. 27 asked people if they would be willing to serve in the U.S. military; 28 asked them if they were willing to give up all allegiance to the Japanese Emperor. Some people thought these were trick questions. Others who did not really worship the Emperor at all wondered how they could give up allegiance that they didn't have. Anyone answering "no" to both questions was gathered up and shipped to Tule Lake Segregation Center, which was a maximum-security center for such "disloyal" people.

Although this is a "young adult" type of book it's a book filled with very good, very concise information and a good introduction to the entire issue of Japanese-American Internment Camps.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|