Japanese-American Internment in American History, 1996

(Note: The book contains far more than I comment on here. I am just pointing out things I found in this particular book that I had not found in other books, or things that further emphasized what I found elsewhere. It's also one of the best books I have found on the subject; very readable.)

The book notes that Earl Warren, who was later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the U.S., was the California attorney general and spearheaded the program to have the Japanese-Americans removed from California.

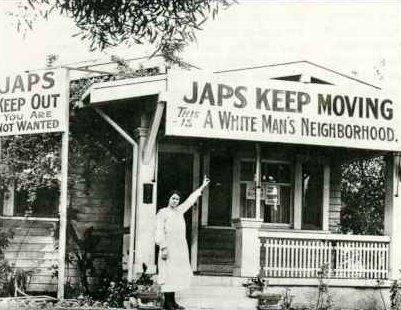

Chinese immigration was halted in 1882. California had a law that did not allow Chinese, African Americans or Native Americans to testify against whites in court. In 1906 San Francisco had all Japanese students removed from its public schools and put into schools in Chinatown.

The book goes on to note many forms of discrimination which Japanese immigrants faced, most of which were similar to those African Americans faced.

Some of the hatred was also eerily similar to that against Jews, who have been hated because of the economic successes their hard work has won some of them. In California, Japanese and Japanese-American farmers worked very hard and did well. The average value of their land in 1940 was $279.96, while the average value of white-owned farmland was only $37.94.

Another interesting law was the Cable Act of 1922. It stated that an Asian woman who married an American citizen was not eligible for citizenship. For a woman it was worse; if she married a person not eligible for U.S. citizenship, she could lose her own citizenship as punishment.

The FBI had already been keeping tabs on Japanese professionals, anyone who was Japanese or a Japanese-American and who was a leader of any sorts. This even extended to Buddhist priests. The FBI raided Japanese-American establishments in Los Angeles and took records and membership lists a full month before Pearl Harbor.

After Pearl Harbor people of Japanese ancestry living in California found their bank accounts frozen, their safe deposit boxes confiscated and there were put on an 8 P.M. curfew.

The Secretary of the Navy tried to claim that Japanese and Japanese-Americans living in Hawaii had aided the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, even though he had absolutely no evidence to indicate any such thing. The commander of Naval Intelligence hired a safe cracker to break into the headquarters of Japanese American groups and go through their papers; he admitted there was nothing suspicious at all. The Japanese-Americans were no more disloyal than anyone else.

A man named DeWitt was the head of the Western Defense Command. His statements about Japanese were nothing short of insane. He stated "We must worry about the Japanese all the time until [they are] wiped off the map.."

He also possessed a wonderful form of logic. He admitted that the Japanese Americans had not sabotaged anything. Therefore, he reasoned, that was absolute proof that they would. In other words, if your neighbor's dog has never bitten you, that is proof that it will.

The book also describes behind-the-scenes arguments between various governmental sections on whether or not there should be any evacuations.

Part of the reason that the evacuations worked against the Japanese but were not used against Americans of German or Italian ancestry was that those populations had strong organizations representing them and established leaders; the Japanese Americans had some organizations but nothing of comparable strength and no really major leaders. What leaders they had were quickly locked up, leaving them without the ability to legally or otherwise fight the effort to have them forced away from the West Coast.

Apparently a week after the evacuation order a Japanese sub fired at storage tanks off the Santa Barbara coast. The following night a weather balloon was mistaken for a Japanese plane and shells were fired, succeeding only in damaging cars when fragments fell from the sky.

Some of the things that state governors said were absolutely shocking. The governor of Wyoming said "If you bring Japanese into my state, I promise you they will be hanging from every tree."

The Japanese Americans and their organizations such as the Japanese American Citizens League stressed that all Japanese Americans should comply with the government so that is why there were no riots or uprisings during the evacuation process.

On June 3, 1942, the Battle of Midway settled the fate of the Japanese Navy and U.S. Naval Intelligence said that the battle effectively ended any threat of the invasion of the U.S. by Japan. Thus, the single reason given for moving the Japanese Americans no longer existed, yet they were still kept in the internment camps.

The U.S. was not the only country that did this. Mexico, Canada and Peru had similar programs. although Peru shipped their people to the U.S..

The camps:

California: Manzanar and Tule Lake

Idaho: Minidoka

Wyoming: Heart Mountain

Colorado: Granada

Arizona: Poston and River

Arkansas: Rohwer, and Jerome

There were problems in the camps. Resentments against the government, the camp administration and even some fellow prisoners would flare up.

Poston: Suspected informer beaten; parents of suspected informer beaten, both cases the beatings being done by other Japanese-Americans.

Manzanar: White employees of the camp stole food meant for the evacuees and sold it on the black market, causing a lot of resentment. One evacuee kept track of the losses, reported them and was thrown in jail. The JACL, who stressed cooperation with the government, was disliked by another group of people who were born in America but educated in Japan.

Some people protested the arrest of Ueno, the person keeping track of the losses, and this led to a confrontation where troops fired teargas at the crowd after someone threw a light bulb at them. Then the guards opened fire, killing two and injuring ten. The government tired to cover the event up, firing the camp hospital's chief surgeon when he refused to alter records from the event.

Tule Lake: The infamous questionnaire with its two confusing questions became a major problem. Many people refused to fill out the form and the camp a number of the second-generation Japanese-Americans were trucked out to local jails. A strike was held of the firing of some workers, then the strike ended. A trunk had an accident, killing one and inuring five. Camp workers blamed the driver and staged a work stoppage.

Striking farmworkers were replaced by workers from other camps and were paid more than the Tule workers. Matters worsened quickly and martial law was declared in the camp. A vote to end the strike resulted in many favoring the strike being rounded up by soldiers and not allowed to vote. The strike ended and martial law was lifted.

The book also describes Japanese-Americans who fought for the U.S. and follows that with an examination of some legal battles over the issue of internment.

Some of the evacuees were able to get out of the camps because they were useful to the government. Interpreters were needed along with farmworkers and college students (if they could find a college that would take Japanese Americans). Others obtained jobs in various eastern and Midwestern states although this sometimes led to problems as in Chicago where Japanese Americans that died were not allowed burial in certain cemeteries, some hospitals refused them as patients and they were absolutely definitely not welcomed back to the west coast.

In 1944 the war situation was improving. The Nazis were being driven back towards Germany and the Japanese armed forces were being driven back towards Japan. The decision was made to end the internment camp program but not immediately. The last camp did not finally close until March 21, 1946, about six months after the end of the war.

Even after returning to the west coast, though, the former internees were still subjected to racial hatred and violence. Some state governments tried to pass anti-Japanese American laws but they either failed to pass or were nullified by the courts.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|