The Japanese take a very serious interest in their tea, so much so that a very formal and elaborate Cha-no-yu, or Tea Ceremony, has been developed.

The earliest record of tea drinking in Japan is from 729 when Emperor Shomu invited a hundred Buddhist monks to the Imperial Palace for tea. In 805 the Buddhist priest Saicho brought tea plant seeds from China and planted them near Kyoto. Some other stoiressay that Kobo Daishi, founder of the Shingon sect, is the one who introduced the tea plant to Japan.

By 816 regular planting of tea gardens had begun. A period of lull followed, though, and in 1191 tea was reintroduced into Japan by Eisai. Eisai was a Buddhist priest who went to China to study Zen. He is credited with re-introducing tea plants and the lore of drinking tea from China. The Way of Tea is said to have begun with him.

The Way of Tea was perfected by Sen Rikyu in the 16th century. When asked to explain the Way of Tea he said there were seven principles to follow:

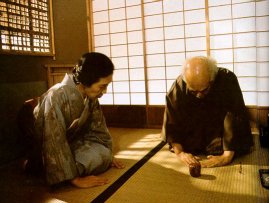

Those might seem simple enough but it is in the perfecting of each of these that the Way of Tea becomes such a complex and beautiful process. The Way of Tea is not something that deals just with a cup of tea set before you. It includes everything that goes into the making, serving and drinking of the tea. The principles said to underlie this ceremony include harmony, respect, purity and tranquility.

The simplicity of the tea room comes from Zen. The Zen approach is to accept the mundane as it is and try to find beauty even in the difficulties of everyday living.

The entire tea ceremony and everything connected with it operates by a very strict set of guidelines. Although the ceremony takes place in a tea house, even the area outside the tea house is important.

Then we come to the teahouse itself. The only entrance to the teahouse will be a small opening, usually about two feet by two and a half feet, requiring the guests to creep through. The design of the teahouse should suggest wabi or the true spirit of the tea ceremony.

There will be slender pillars made from natural logs, small windows with grilles of bamboo and shoji or sliding doors covered with paper. The ceiling will be low and of irregular height.

The house is divided into the tearoom proper, built to hold a maximum of five guests, and a mizuya or water-room with a pantry for preparing the tea and washing the utensils. The area of the tearoom proper will be about four and a half tatami in size. In one corner will be a square hearth sunk into the floor with an iron kettle.

The tea ceremony can be informal in nature and last about an hour or be the full formal mode and last around four hours. In the short form only powdered tea is served. In the long form there will be some food (kaiseki) followed by a thick pasty tea (koicha), and finally a foaming tea brew called usicha.

There are also certain times during the day that the ceremony should be held. One is yogomi which means overnight and is held at 5 A.M. in the summertime. Morning tea in the winter is served at 7 A.M. The summertime hour is chosen for appreciation of the flowers/plants used for decoration and the winter time is chosen since this is considered the time best suited to enjoy the air in all its freshness and appreciate the beauty of newly-fallen snow.

For a formal cha-no-yo invitations are sent out at least a week in advance. The guests are expected to reply to the invitations promptly. Those accepting are expected to visit the host the day before the ceremony to express their appreciation at being invited.

The host of the ceremony has to consider virtually every aspect of the ceremony and where it is going to take place. The host must decide on the food that will be served, on floral arrangements, and on kakemono or hanging scroll that will be present. Just before the ceremony is to take place the host must also sweep the garden and its path, sprinkle the path with water, make sure the tea room and the rest of the area is extremely clean and also has to arrange the tea utensils in the proper order.

This does not mean that it is the host alone who has things to do to properly prepare for the ceremony. The guests also have their own preparations. The men are expected to wear a black silk kimono with three or five family crests on it, a divided skirt (hakama) and white tabi (socks). Women also wear a kimono with crests and white tabi. The guests also are expected to bring a small folding fan, a couple square pieces of sillk and a pad of white paper on which to place any cakes served.

The guests arrive about a quarter of an hour before the appointed time.

They assemble in a small waiting room. An assistant to the host appears and bows and gives each guest a cup of hot water for them to drink. The guests them move to the waiting bench outside the waiting room.

Next to consider is the order the guests will enter the tea room. This might be decided by the host in advance or the guests themselves might decide it together. The main guest is chosen for his or her knowledge of the tea ceremony and will serve as the group's spokesperson. The main guest will lead the group into the tea room.

The guests might also announce their presence by knocking on a wooden gong provided by the host.

The host makes a last-minute inspection to make sure everything is ready and then goes out to meet the guests. The host will bow to the guests, they will return the bow and then they will go into the tea room. The garden area that they will pass through is set up to help establish a feeling of peace and tranquility.

Near to the tea room the guests will find a stone water basin where they will ritually cleanse themselves, cleansing their hands and rinsing out their mouths. The same type of basins are found near Shinto shrines.

The guests remove their sandals and then creep through the door into the tea room. They will kneel before the tokonoma to show their respect.

A tokonoma is an alcove which is a form of shrine. It is a place of honor where a hanging scroll (kakemono and flowers are put so their aesthetic qualities might be appreciated. The scrolls might be of calligraphy, or inkpaintings of landscapes, figure subjects and other themes of Japanese life. The type of area is very important and will be found in living rooms of larger houses along with their presence in the tea room. The place of honor in a Japanese room is the area in front of the tokonoma. The tokonoma is thus a place that is both sacred and aesthetically beautiful.

(The kakemono, or hanging scroll, had its origins in China. It is a painting on silk or paper, mounted on a vertical scroll. backed with heavy paper and sometimes with other things to strengthen its framing. One form has a poem or verse written on the painting. The kakemono are changed with the seasons and sometimes on cremonial occasions.

The Japanese room might also have a kamidana which is a Shinto altar located on a shelf high up in a corner of the room. It might include an architectural reproduction of a Shinto shrine. The kami (deity) is represented by a small sacred tablet on which is written its name, the tablet being placed in the miniature shrine or on the shelf itself. In the anime series Ranma 1/2 a kamidana is seen frequently in the dojo. One time it falls off the walls and the people there take that as a bad omen.

After the guests have finished admiring the tokonoma they then admire the portable brazier or the sunken hearth with its kettle. They then take their places with the principal guest being seated before the tokonoma.

The host then comes out of the mizuya or the room where the utensils are cleaned and arranged. The main guest greets the host and expresses thanks for having been invited to the ceremony. The other guests also greet the host and then the main guest asks about the garden and the kakemono that hangs in the tokonoma.

After the exchange of greetings the guests (in the full-length tea ceremony) will be served a kaiseki. This is a small meal with certain dishes served according to a fixed order. The host brings in the dishes and serves them, although he or she does not eat. The dishes in order are:

1. A soup made of soybean paste and served in a lacquer bowl.

2. Rice is served in a lacquer bowl.

3. Raw fish or shellfish (mukozuke) are served in a porcelain dish.

The three dishes are brought into the room on a square-shaped lacquer dinner tray called a ozen.

Even the eating of the food is ritualized. The principal guest's actions are duplicated by the rest of the people in attendance as he or she uncovers each bowl using both hands and then placing the covers beside the trays. The soup and rice is eaten and then the covers replaced. A metal sake pot called a kannabe and shallow sake cups are brought in, the sake to be drunk when the guests are eating the mukozuke. More rice is brought in and another bowl of the bean-paste soup.

4. Vegetables and boiled fish (imono) are next and are also served in a lacquer bowl along with another serving of sake.

5. A plate or two lacquered boxes are then brought in which contain yakimono or broiled fish and vegetables. Another serving of rice and a bowl of clear soup are also served.

The host then removes the lacquered boxes or plate and the wooden rice vessel and takes them to the pantry.

6. The next course is called hassun and has two delicacies, one from the sea and one from the soil. A pot of sake is brought in nd the host asks if he or she may have the honor of drinking from the cup of his guests. The host serves the hassun to the main guest, filling his cup with sake. The main guest drinks the sake and gives the cup back to the host so the guest can then fill the cup.

7. A large lacquer vessel with a sprout is then brought in. This contains hot salted water and boiled rice. Some pickled delicacies are also brought in on a plate. The watered rice is poured into the bowls of the guests and is then eaten along with the pickled items. Once the food is eaten the bowls still on the guests plates are wiped clean and their chopsticks are placed onto the tray.

8. Sweets are then served, brought out on trays one at a time by the host.

Once this part of the tea ceremony is done the guests retire to the waiting room or to an outdoor roofed arbor. Here they relax until the second part of the ceremony begins. The host strikes a gong, indicating to the guests that the next part is ready and they return to the tea room.

The guests again purify themselves at the stone basin and then reenter the tea room in order. While they were gone an arrangement of flowers was placed onto the tokonoma, replacing the hanging scroll. They admire the flowers and again admire the kettle or the hearth, depending on which is used.

The host then sits by the hearth with the various tea-making utensils arranged nearby. These include:

The chawan or tea bowl.

The chaire or tea caddy.

The mizusashi or water jar.

The chasen, the bamboo tea whisk which is used to beat the powdered green tea in hot water.

The chashaku, the very thin bamboo spoon used to move portions of tea from the tea caddy to the tea bowl.

The chaikin or tea cloth, used to wipe the tea bowl.

The koboshi or kensui, a receptacle for waste water.

The hishaku, the bamboo ladle used for the water in the kettle.

The futa-oki, a small article of porcelain, metal on bamboo on which is placed the cover of the kettle or the ladle.

The fukusa, small pieces of silk.

The second part of the full-length formal tea ceremony starts with koicha which is a thick pasty green tea. A receptacle containing small cakes is placed before the main guest. The host then wipes the teaspoon and tea caddy with his fukusa. He then pours hot water from the kettle into the tea bowl, using the bamboo ladle to wash the tea whisk. The tea bowl is then emptied by pouring the water into a waste-water bowl and the tea bowl is then wiped dry.

Two or three powdered spoonfuls of the tea for the koicha service are mixed with water and then whipped to a creamy froth with the bamboo whisk. When the host decides that the tea is ready he puts it into teh bowl situated in front of the main guest.

Now the ceremonial emphasis moves to the main guest. The guest picks up the tea bowl and holds it on a fukasa in the palm of his left hand, supporting one side with his right hand. He then rotates the cup clockwise three times with the right hand then drink the tea, stopping after the first sip to compliment the host on its fine preparation. He ten takes two or more sips, then wipes off the part of the cup that touched his lips, rotate it counterclockwise and then passes the bowl to the second guest who repeats the process, passing the bowl on to the third guest and so forth.

The host then washes the teaspoon and the tea whisk, pours a ladleful of water into the kettle and replaces its lid.

The last part of the full-length tea ceremony also serves as the shorter-length tea ceremony in and of itself. In this ceremony a thin foamy green tea called usucha is used. This tea is made from the young leaves of plants three to fifteen years old as opposed to koicha which is made from plants twenty to seventy years old.

The ceremony proceeds similar ot the koicha ceremony. After the tea has been drunk the main guest asks the host if he can examine and admire the tea bowl.

After this is all done the guests leave through the small door and return to the waiting room. On the next day each guest is expected to send a letter to the host or visit the host, thanking him for the privilege of attending the ceremony.

Hatsu gama refers to the first Tea Ceremony of the year.

Some types of tea

Bancha: this is everyday tea

Gen maicha: a tea with toasted rice kernals which add a nutty flavor

Gyokuro: a tea made with tender young leaves grown sheltered under reed screens. It is a tea for the connoisseur and is served with sweets.

Matcha: powdered green tea used exclusively in the tea ceremony.

During the late Muromachi period there was a new school of tea ceremony called Wabi which arose, emphasizing rustic simplicity.

The Ten Virtues of Tea

When the Zen monk Eisai brought tea seeds from china to Japan in the twelfth century, he also imported the following ten virtues of tea.

It has the blessing of all deities.

It promotes filial piety.

It drives away evil spirits.

It banishes drowsiness.

It keeps the five internal organs in harmony.

It wards off disease.

it strengthens friendship.

It disciplins body and mind.

It destroys all passions.

It gives a peaceful death.

Lacquered tea container; tea bowl; bamboo whisk and scoop for some of the instruments of the tea ceremony.

Sen no Rikyu's Seven Rules of Tea

Arrange the flowers as they are in the fields.

Lay the charcoal so it boils the water.

Create a cool feeling in summer.

Make sure the guests are warm in winter.

Be sure everything is ready ahead of time and do not fall behind.

be prepared for rain even if it is not raining.

Always be mindful of the guests. They're your first, your last, your everything.