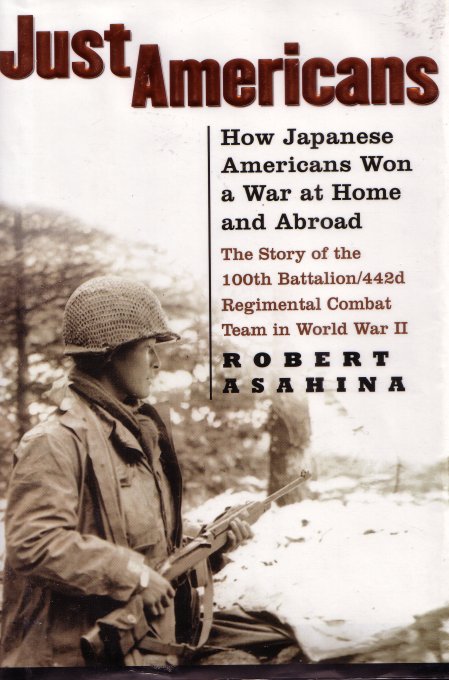

Just Americans: How Japanese Americans Won a War at Home and Abroad (2006)

In October, 1944, there were four companies of a Texas Division of soldiers who were stranded in eastern France behind enemy lines. They were without reinforcements or supplies, but they ended up being rescued by the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was composed of Nisei, men of Japanese ancestry.

The 442nd “had participated in seven major campaigns in Italy and France, received seven Presidential Distinguished Unit citations, and suffered 9,486 casualties and was awarded 18,143 individual decorations, “ all within a period of less than two years.

Their motto was “Go For Broke.”

More than 22,500 Japanese Americans served in the Army in WWII, 18,000 of them in segregated units, most of the rest used in the Pacific theater as translators.

Keep in mind, though, that this was at a time when many of their families were being kept behind barbed wire in internment camps on the US mainland. The people had not been charged with any crime, yet their rights were taken away from them and they were basically treated like criminals.

Once Pearl Harbor was attacked, things changed radically for the persons of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii, but not as radically as those who lived on the West Coast. Lt. Gen. Delos Emmons, the military commander of the islands, considered evacuation and relocation of the persons of Japanese ancestry living in Hawaii, but instead of making a quick decision he talked to others and realized that evacuation and relocation wasn't necessary or practical.

The main thing was that the persons of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii were more integrated into the American culture than were those living on the West Coast. The reason for that deals mainly with prejudice; the AJA (Americans of Japanese Ancestry) who lived in Hawaii did not have to deal with anywhere near the level of prejudice those on the West Coast did. The AJAs in Hawaii formed about a third of the population, and they were major factors in the economics of Hawaii. The AJAs on the West Coast, though, had been disliked and hated for years; they white farmers were jealous of how successful the AJA farmers were, and the so-called community leaders often took strong anti-AJA stands along with the newspapers.

So the AJAs on the West Coast were never really given a chance to fully integrate into the larger “American” society, while those in Hawaii were able to.

On May 28, 1942, Emmons was ordered to reorganize Japanese American soldiers into the 298th and 299th provisional battalions. The groups a week later had sailed to San Francisco, where they were then called the 100th battalion, and then shipped to Wisconsin for training.The book also describes the differences between the AJAs from Hawaii (the “Buddhaheads” and the AJAs from the mainland (the “kotonks.”) The two groups did not get along at all well at first. They had rather different cultures that tended to clash.

The book also talks about the “no-no's” caused by the controversial questions 27 and 28 on a questionnaire, and how they ended up at the Tule Lake internment camp. There is also a discussion of the call for volunteers, and how more AJAs from Hawaii volunteered than did AJAs from the US, which is not surprising considering they and their families were in internment camps.

May, 1943. Assistant Secretary of War McCloy says “there [is] no longer any military necessity for the continued exclusion of all Japanese from the evacuated zone.” Still, the internees were not free to return and were not wanted.

The book points out that in the six months after Pearl Harbor, Nazi subs sunk 185 ships off the East and Gulf Coasts of the US, yet there was no cry to intern persons of German ancestry in the Eastern US.

FDRs plan was basically to disperse the persons of Japanese ancestry throughout the United States and not allow them to remain concentrated on the West Coast. Thus, the internment program was actually partially a social program to force the relocation of an entire race of people. This could have been planned to help them assimilate, or it could have been planned as a means of destroying the unity of the Japanese American community with the eventual goal of “phasing out” that community.

One reason for not allowing the internees to return earlier to the West Coast was that there was an election year and FDR didn't want to stir up any political on the West Coast by releasing the internees and allowing them to return to their former homes.

Problems arose when there was an effort to draft some of the internees. This caused a lot of personal difficulties. Here they were, locked up behind barbed wire, their homes gone, their jobs gone, and they were expected to respond positively to an order to fight, and maybe die, for the country that was denying them their rights as American citizens. The men would have to decide whether to go along with the draft or refuse to and take the consequences.

The book then goes into a lot of detail about the 100th Battalion and their fighting in Europe. The book is worth buying just for this section alone.

In November of 1944 “...the American Lesion post in Hood River, Oregon, erased the names of sixteen Japanese American soldiers from a memorial honoring servicemen from the area.”

The move was denounced by the Secretary of War, Stimson, who called it “wholly inconsistent with American ideals of democracy.”

The commander of the Salinas Valley American Legion said “We don't want Japanese here and we said so bluntly in a recent resolution. There appears nothing we can do about it however.”

”Within the first five months after the announcement that the 'relocation centers' would be closed, incidents of violence against returning Japanese Americans 'had reached such proportions that Secretary Ickes issued a public statement denouncing the perpetrators and demanding more effective protection for the returning evacuees.”

The East Coast, on the other hand, was much more open to the returning of the evacuees, and the 442nd got a “hero's welcome” in New York City.

Main Index

Japan main page

Japanese-American Internment Camps index page

Japan and World War II index page

|