How to Think

I will be adding my own comments, by the way.

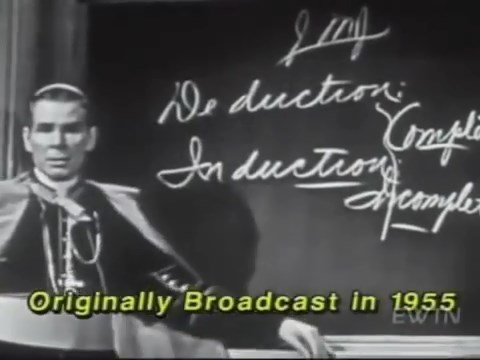

He says there are two general ways of thinking, deduction and induction. Deduction is from the universal to the particular. Example: all men are mortal. John is a man. Therefore, John is mortal.

Induction is from the particular to the general or universal. Statistics are useful in this. Investigation is necessary in this form of thinking. Induction can be either complete or incomplete, depending on what proportion of the samples you have checked. There are very few that are actually complete.

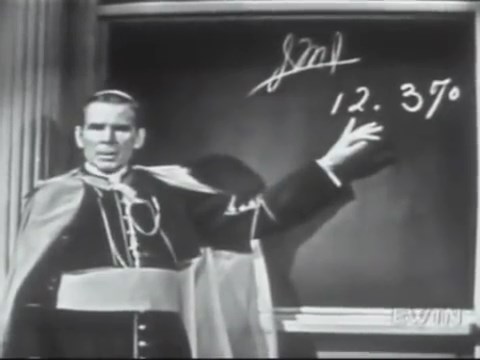

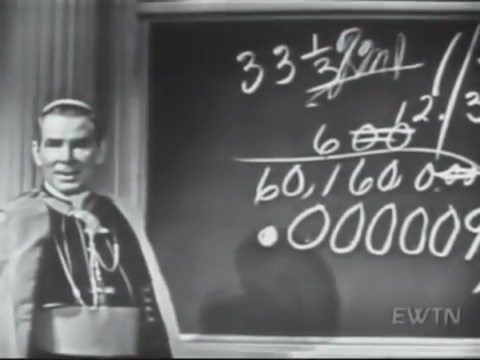

Then he starts into an examination of statistics. The 12.3% is an example such as what percentage of people under 21 say their prayers. It seems quite blatant but it's totally misleading. Then he goes into questions you should ask yourself whenever you hear a statistic.

1. How many possible cases are there? For example, if there are only 20 samples of something and you check 19 of them then you have a good chance of arriving at a logical and accurate conclusion. If you only sample 3 of them, though, your conclusion could very well be wrong.

2. How many cases were tested? This relates to what is written above.

3. Can you believe what they told you?

4. If it comes from an independent laboratory, who paid for the experiment? Both 3 and 4 relate to who did the investigation and why did they do it. Are they totally objective or do they have some preconceived notion they are working with. Does the company that paid them expect a certain result that will benefit the company.

Further, in any article you read about a statistic, are any of these questions answered.

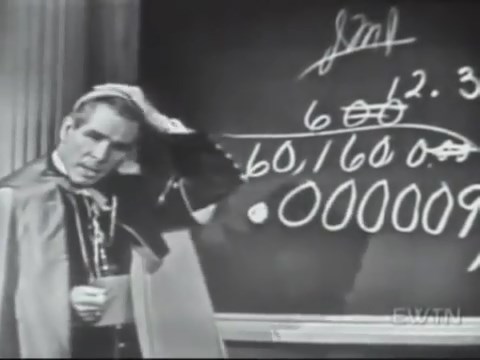

This is an example of #1. If 600 cases are checked but the total population is as on the board, then the study has checked much less than even 1% of the possible cases which basically makes any conclusions utterly undependable.

He talks about an actual article that said one-third of the women at John Hopkins in a certain year married their professor. However, and this is a very big however, there were only 3 women at the university at that time and only 1 of them married a professor. This throws any conclusions made from the first part into the garbage bin. Statistics can, without doubt, be totally misleading and undependable.

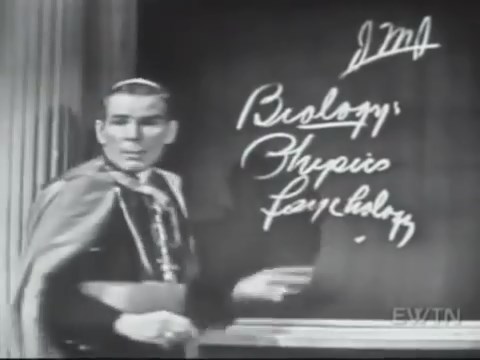

Then he talks about not following moods/fashions of the times. What he's saying is that you cannot necessarily take conclusions from one science or whatever and apply them directly to another science or whatever.

He gets specific. He says you can't take the conclusion from biology that everything is evolving and apply it to theology and say therefore God is evolving. This is one of the things that is overlooked today. Further, if someone makes a statement X then the question should become is that person qualified to make that statement. If a doctor says X, for example, the question should be is that X part of the doctor's special emphasis? How long has doctor been a doctor? If you want to get very specific, then you could even ask where did he graduate in his class and what has he studied since then.

Say lawyer Y is quoted for something major. If lawyer Y graduated near the top of his class and has continued his study of law since then he or she is more believable than lawyer N who graduated near the bottom of the class and hasn't made much of any study at all in law since then.

He also points out that fashions and moods change over time. For a very long time in human history it was thought that the Earth was the center of the solar system and the sun and all the planets revolved around it. People who said otherwise got in trouble like Galileo. With more data over a long period of time we know for positive that the sun is the center of our solar system and the Earth and the other planets go around the sun.

He says to think well means you need principles that are independent of space and time (fashions/moods, etc.) He says we know certain principles exist because there is an intelligence behind the universe.

Let's take one of the major problems today and that is the battle (by some people) between science and religion. You can get strong feelings on both sides (such as the Scopes Monkey Trial.) Yet the two have very, very major differences in how they arrive at what they consider truth to be.

Science is based on observation. Experiments to learn about things must be able to be replicated by other scientists who reach exactly the same results. You have three levels of science. First is the hypothesis, an educated guess. If, for example, you eat something and later in he evening feel sick to your stomach then your hypothesis is that the food you recently ate is what made you ill.

A theory is the next level up and this is where an idea has been tested a bunch of times and seems to be true. (This is where statistics and the principles Bishop Sheen noted above come in.) If you have the same food three days in a row and you get sick each day then it's very probably what you ate that made you ill.

Still, there could be something else that would explain your illness. Doubtful but still possible.

The highest level is the Law which is something that is true 100% of the time everywhere in the universe. There aren't a whole lot of these.

Religion, on the other hand, is based on faith. The principles of various religions may differ. They can't necessarily be tested in a laboratory over and over with the exact same results each time. There's a tremendous amount of personal belief that comes into play and that belief could have been prompted by things you learned when you were young or perhaps by things you've seen, heard or read when you got older. Your beliefs might change.

True scientific laws don't change. Theories may change. Hypotheses can frequently change.

So when you are considering a particular issue it's a good idea to know what approach the person is taking when they talk about the issue. Are they backed up by definite facts? Or is what they say based only on their beliefs?

Thinking can take a lot of work. But it's worth it.

Back to start of Spirituality section

My Index Page

|

|