The Octoroon

First, what is an "octoroon?" It's a person who is 1/8 th Black, according to the dictionary, and the term comes from the Spanish.

The play takes place on a Louisiana plantation and Maude Adams plays "Little Paul", a mulatto boy. The boy is sent down to meet the river boat and get the mailbag. Mrs. Peyton is the widow of the judge who owned the plantation and is not a joint-owner with their former overseer Jacob who is also cast as the villain.

The new overseer, who is also a photographer, is also a bad person and his actions have ruined the estate.

It turns out that the mail contains repayment of a loan that the judge had made to a Liverpool firm. Paul dawdles on the way back with the male and sits on the mailbag to rest. Jacob wants the money and kills Paul but the overseer's camera is somehow triggered and catches the event on film.

=====Impossible Purities: Blackness, Femininity, and Victorian Culture by Jennifer DeVere Brody; Duke University Press, 1998=====

Zoe Peyton, the central character in Dion Boucicault play, The Octoroon , or Life in Louisiana , which opened in New York in 1859, is the supposedly freed "natural" daughter of a Judge Peyton, who owns the Louisiana plantation, Terrebonne, where the drama takes place.

In this melodrama, the heroic lovers, Zoe and the judge's prodigal nephew, George, are thwarted in their quest for romantic love by the evil machinations of a monied overseer named Jacob M'Closky. M'Closky covets Zoe and Terrebonne, and contrives a way to buy both; in the last act, however, a "good" overseer, Scudder, a "Yankee and Photographic Operator," provides evidence -- in the form of a photograph of M'Closky murdering a young slave -- that hastens the play's denouement.

Zoe, like Rhoda Swartz, has "the education of a lady" (act 1); yet unlike Rhoda, Zoe's wild black roots have been trained and thoroughly tamed so that she is virtually a white lady. Although the purely passionate Zoe, the tragic heroine, is the product of the judge's illicit adulterous affair with a quadroon slave, she is reared by the judge's white widow. While long-standing American antimiscegenation laws made marriage between blacks and whites impossible, it did not expressly forbid "merely" sexual relations between them. The exogamous arrangements represented in Boucicault's play were a normal part of the "peculiar institution," if not their very raison d'être. Such forms of amalgamation were seen as one of "the customs of Louisiana," where in mid-nineteenth-century New Orleans, adultery with octoroon fancy girls was the presumption (if not the requirement) of gentlemanly status. Such illegal couplings undergird the belief that the octoroon's story was inherently dramatic since it was ipso facto concerned with illicit desire, seduction, and anarchy.

Boucicault describes the origins and import of the octoroon's story as follows:

The word Octoroon signifies "one-eighth blood" or the child of a Quadroon by a white. The Octoroons have no apparent trace of the Negro in their appearance but still are subject to the legal disabilities which attach them to the condition of blacks. The plot of this drama was suggested to the author by the following incident, which occurred in Louisiana and came under his notice during his residence in that State. The laws of Louisiana forbid the marriage of a white man with any woman having the smallest trace of black blood in her veins. The Quadroon and Octoroon girls, proud of their white blood, revolt from union with the black and are unable to form marriages with the white. They are thus driven into an equivocal position and form a section of New Orleans society, resembling the demi-monde of Paris. A young and wealthy planter of Louisiana fell deeply and sincerely in love with a Quadroon girl of great beauty and purity. The lovers found their union opposed by the law; but love knows no obstacles. The young man, in the presence of two friends, who served as witnesses, opened a vein in his arm and introduced into it a few drops of his mistress's blood; thus he was able to make oath that he had black blood in his veins, and being attested the marriage was performed. The great interest now so broadly felt in American affairs induces the author to present "The Octoroon" as the only American drama which has hitherto attempted to portray [sic] American homes, American scenery, and manners without either exaggeration or prejudice. The author has been informed of the strong objection to the scenes in this drama representing the slave sale at which Zoe is sold and to avoid her fate commits suicide. It has been stated that such circumstances are wholly improbable. In reply to these remarks he begs to quote from slave history the following episode: a young lady named Miss Winchester, the daughter of a wealthy planter in Kent had been educated in Boston where she was received in the best circles of society and universally admired for her great beauty and accomplishments. The news of her father's sudden death recalled her to Kentucky. Examination into the affairs of the deceased revealed the fact that Miss Winchester was the natural child of the

planter by a quadroon slave; she was inventoried in chattels of the estate, and sold; the next day her body was found floating in the Ohio [River].

Like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, Boucicault justifies his script by citing an episode from "slave history." This quotation is notable also for they way in which it explains the "equivocal position" of the white-appearing octoroons as a result of the pride in their white blood. Because of the octoroon's valued whiteness, they logically must "revolt from union with the black." Thus, the real problem is that these desirable (because white-appearing) young women are prevented from marrying white men. This aspect of Boucicault's drama signals a shift toward a marked concern with "white slaves" -- not only to enslaved "white" octoroons such as Zoe, but also, and more important, to any "white-appearing" (and therefore presumed white) women who were mistreated. The horror of slavery, therefore, was increasingly emblematized by the degradation suffered by "white" women.

There is no doubt that Zoe is a lady; and yet, because she is one-eighth black, she is seen as being luxurious. Zoe is the supreme object of desire. "Niggers [sic] get fresh at the sight of her. . . , the overseer M'Closky shivers to think of her," and George, the judge's nephew, is captivated instantly. She becomes the common denominator between these disparate men; yet only the southern hero, George -- a perfect specimen of the aristocratic planter class -- is deemed worthy of Zoe's love. In this way, Boucicault may have played to southern sentimental family values that worked to cover over the raw economics of slavery.

The New Orleans fancy girl auctions serve as the most blatant reminder that the nation's formation is inextricably bound up with (dark) female subjects. As Joseph Roach explains, the auctions, which took place in the rotunda at New Orleans' famous St. Louis Hotel, were staged as "competitions between men . . . [and] seethe[d] with the potential for homosocial violence. As theatrical spectacle, [the auctions] materialize the most intense of symbolic transactions in circum-Atlantic culture: money transforms flesh into property; property transforms flesh into money; flesh transforms money into property." The first scene of the play allows, and even elicits, potential "buyers" in the form of the audiences who have paid money to see the white actress Agnes Robertson perform the part of Zoe and to look at her body. Moreover, we must remember that the audiences no doubt attempted to scrutinize her body for signs of her buried "black" life. As dramatic strategy, the signs of Zoe's blackness are staged in a way that -- unlike a film, where the camera could zoom in for a close-up of the blue tinge of the actress's fingernails -- the audience must imagine how her "deviant" difference might be written on her body.

Zoe changes her status in the play. In act 1, she believes that she is free and then finds out that she is a slave. The mixed-race heroine undergoes several transformations in which her contradictory body is pushed and pulled between its multiple significations. Zoe is free, then slave, then free again -- the last time permanently in death. She "falls" in status. Ironically, Zoe's fall (her transformation from free woman to slave) is represented at the play's climax, in which she stands on top of a table -- elevated above both the fleshmongers who bid on her body and the other black characters in the play. This staged inversion of the dominant codes reveals how value is inscribed on Zoe's body. She is, in fact, more valuable (as were the fancy girls) when the blackness of her body is performed in this manner. "The body of the white-appearing Octoroon . . . offers itself as the crucible in which a strange alchemy of cultural surrogation takes place. In the defining event of commercial exchange, from flesh to property, the object of desire mutates and transforms itself, from African to Woman."

When the hero, George Peyton, declares his love to "African-derived" Zoe (and not to the white woman Dora Sunnyside), he says, "Love knows no prejudice" and offers to marry Zoe, despite the fact that she is illegitimate. Zoe expects George's response to follow Shakespeare's lines: "My thoughts and my discourse as madmen's are, / At random from the truth vainly expressed: / For I have sworn thee fair, and thought thee bright, / Who are as black as hell, as dark as night." George has been "educated in Europe and just returned home" . No doubt his European education, if true to gentlemanly form, included trips to brothels, as was de rigueur for those taking the grand tour. Indeed, George's sojourn in Paris -- the land of the sexually adventurous French -- was meant to be an initiation into a man's world. We learn that "all the girls were in love with him in Paris, and he even admits that he has been in love 249 times. Scudder alludes to this fact when he comments on George's admiration of Zoe's beauty. He states, Guess that you didn't leave anything female in Europe that can lift an eyelash beside that girl" or "who is more beautiful and polished in manners" . Indeed, Zoe proves herself to be a lady not only in appearance, but also in fact, honorably informing George of her maternal heritage.

a dramatic moment, Zoe declares herself "an unclean thing, forbidden by the laws", and asks for George's "pity." George, who is ignorant of American antimiscegenation legislation, is mortified to learn that the object of his desire cannot be recognized as his legal wife. Zoe points out the "bluish tinge under her nails and around her eyes as evidence of her Black" maternal roots, and states that "the dark fatal mark . . . is the ineffaceable curse of Cain." Her solution to this dilemma is to commit suicide at the end of the play. Here, the disjunction between literal and figurative blackness is questioned by Zoe's peculiar person, underscoring the extent to which race must be understood as "performative." That is to say, the law that labels Zoe literally black, possessing black blood, is undercut by its clearly figurative use. In appearance, manner, and form, she is not "black"; her blackness must be written on her. It is her belabored confession that "delivers" her blackness.

The ontological assurance of what blackness "is" is never guaranteed in the play. Indeed, it is the purpose of the octoroon to pose (as) the problem of racial discernment. While her paradoxical social placement is clear from the beginning of the play, it is continually and more overtly confirmed during the play's performance. The inevitable drive toward Zoe's degradation (and increased gradation) is heightened by the presumption in the first act that she is free. In act 2, she learns that, in fact, she is enslaved. The massive contradictions that underwrite the play work to delegitimate certain societal values. The oppositions of slave and free, white and black are disrupted when figures such as Zoe enter the dominant national, familial structures. Read as disrupting forces, they must be destroyed.

In Boucicault's original version, performed in New York in 1859, Scudder's discovery comes too late to save Zoe from suicide; in another version of the drama, presented in London two years later, Zoe lives and, in the final tableau, is swept up in George's arms. In the English version of Boucicault's drama, Zoe ends up with her lover, an American man (merely of English descent), with whom it is declared "she will solemnize a lawful union in another [unspecified] land."

In the American version, Zoe reacts to her fate by drinking a suicidal poison, like Shakespeare's Juliet. This action relieves her from becoming a slave and the property of the vile M'Closky, and is presented as the noble choice, since she lost her opportunity to become the wife and property of the aristocratic hero, George Peyton. She opts to go to the "free" land so often celebrated in "Negro" spirituals. She is purified in death. Zoe's ingestion of the poison is an attempt to solidify her body formally -- to make her taint more permanent. If she has been "poisoned" with the blood of her African American mother, then she replicates this "original sin" for George. At the end of the play, however, the script says that she turns "white" -- again following the typical trajectory of the octoroon.

The difference between the two versions points to the very different politics of race in the two nations. English audiences, who were at a remove from the direct, systematic, and legal divisions of racial conflict, could radically rewrite the octoroon's narrative. As Boucicault reported in a London playbill from 1861: "Mr. B. begs to acknowledge the hourly receipt of so many letters entreating that the termination of the Octoroon should be modified and the slave heroine saved from an unhappy end. He cannot resist the kind feeling expressed throughout this correspondence nor refuse compliance with the request so easily granted. A new last act of the drama composed by the public and edited by the author will be represented on Monday night." In the first version of the play, Zoe enacts her understanding of cultural binaries and her low other position vis-à-vis such boundaries. Furthermore, she decides to maintain and not transgress such boundaries. In the English version, however, she allows George to follow his heart, even at the expense of breaking the law. That true love triumphs is the stock-in-trade of melodrama; but even here, the implied blissful future of the lovers is not guaranteed.

Their reconsolidation is also undercut by the fact that in all versions of the drama, Agnes Robertson, a white woman and Boucicault's wife, played the part of Zoe, ensuring that an "actual" interracial kiss did not occur -- only an apparent (or a white-parented) woman can portray purity properly as a property only of "whites." Boucicault's decision to cast his wife in the lead role of the octoroon resonates with Robertson's repertoire. Before this part, she had a reputation for playing breeches roles (in which female actresses wore trousers for part of the production) with great panache. Known also for the acumen with which she performed multiple parts in a single drama, Robertson seemed to be the perfect figure to dramatize the destabilized body of Zoe. In this regard, she epitomized Victorian actresses, who used disguises to change themselves and to emphasize the fact that women's bodies, like viscous material, can be malleable and cannot be contained.

An example of this illicit desire between father and daughter is hinted at in Boucicault The Octoroon. The dialogue in the drama makes continual references to the young Peyton's striking similarity to his dead uncle, the judge, who is Zoe's father, therefore making the nephew Zoe's cousin. This family resemblance provides evidence of the "incest" that is read as being coterminous with "miscegenation" and other forms of illicit amalgamation.

Some nineteenth-century thinkers elided the differences, between incest, miscegenation, and adultery, and placed these phenomena in the common category of the illegitimate or culturally anomalous. These confused and confusing categories are consistently juxtaposed with a pure and proper one, namely, the nuclear family epitomized by white Christian marriage. If the proper family is the building block of a strong nation, then incest, miscegenation, and hybridity threaten the family (of man), and by extension, the nation (of proper gentlemen). The precarious sexual nature of women who are not wives and mothers, like Zoe, complicates the pure and proper perpetuation of this national family. Victorian conventions (predominantly promoted by middle-class men) about female sexual transgression impose borders by systematically classifying and differentiating between pure women and passionate women, between licit and illicit sex.

The Octoroon is continually concerned with the maintenance and production of civilized subjects, and ultimately, the Christian characters prevail.

=====The Harlem and Irish Renaissances: Language, Identity, and Representation by Tracy Mishkin; University Press of Florida, 1998=====

Early comparisons of a sort also occurred in Irish literature. Four days after the hanging of John Brown in 1859, a play by the prolific and popular Irish playwright Dion Boucicault entitled The Octoroon; Or, Life in Louisiana opened in New York. The Octoroon was a melodrama that aimed to please pro- and antislavery factions: the author presented both bucolic plantation scenes and the horrors of slavery. Although Boucicault straddled the fence on the slavery question, the play differed enough from standard nineteenth-century depictions of African Americans for Montgomery Gregory to praise it in Plays of Negro Life. Gregory wrote that The Octoroon represented a welcome respite from the flood of minstrel shows popular in the second half of the nineteenth century, as it "accustomed the theatre-going public to the experience of seeing a number of Negro characters in other than the conventional 'darkey' rôles" . Gregory exaggerated: the title character, Zoe, is the only non-"darkey" character, although one was enough to infuriate a New York theater critic who pronounced the play abolitionist propaganda and Zoe an impossible creation.

Since Gregory's comments in 1927, other critics have also distorted Boucicault's, attitudes and accomplishments, overstating the degree to which he perceived a connection between Irish and African-American oppressions. For example, biographer Richard Fawkes stated that "[a]s an Irishman, a member of a subjugated nation, Boucicault felt keenly the indignity of slavery, of one race being beholden to another" . Fawkes does not successfully substantiate this claim with Boucicault's writings. In fact, in an 1861 letter to the London Times , Boucicault claimed that his years of residence in Louisiana had shown him that slavery was not as terrible as the abolitionists asserted: "I found the slaves, as a race, a happy, gentle, kindly-treated population, and the restraints upon their liberty so slight as to be rarely perceptible" . Fawkes only quotes part of this letter, making Boucicault appear more opposed to slavery than he was. It may not be a coincidence that Boucicault's plays written in the decade or so after the production of The Octoroon included his most famous Irish comic political melodramas, The Colleen Bawn , Arrah-na-Pogue , and The Shaugbraun ; however, the assertion that Boucicault explicitly connected African-American and Irish oppressions remains conjectural.

=====The Bishop of Broadway: the Life & Work of David Belasco by Craig Timberlake; Library Publishers, 1954=====

Famous stars graced the Opera House stage and Belasco momentarily forgot his acute financial distress in the contemplation of such distinguished figures as Edward A. Sothern in his famous role of Lord Dundreary, Mrs. D. P. Bowers, and Dion Boucicault and his wife, Agnes Robertson. Belasco served for a short period as amanuensis to Boucicault and much has been made of the supposed influence of the prolific English dramatist on his young American admirer. Boucicault was a gifted constructor of frankly melodramatic plays, many of which were translated from the French or adapted from successful novels. With his play The Octoroon; or Life In Louisiana, written in 1859, he became the first successful playwright to deal seriously with material involving the American Negro

The play unfolds the tragic story of an octoroon beauty named Zoe who cannot marry the white man she loves. Boucicault avoided giving offense to North or South. His slavery is not inhumane and his Negro figures are cheerfully indolent and carefree. The audience was allowed a choice of two separate endings, a novelty which no doubt contributed to the great success of the play Belasco may have benefited by this close association and firsthand observation of a renowned playwright's methods. In a few years he was earning a modest success at the games of piracy and adaptation that produced many of the stage vehicles of the time.

=====A History of Late Nineteenth Century Drama, 1850-1900 Vol. 1 by Allardyce Nicoll; Cambridge University Press, 1946=====

By the close of the fifties, however, Boucicault was sensing the necessity of a change, if not in theme at least in outward semblance. Out of these historical or pseudo-historical romances grew the plays which, after all, form his most characteristic contribution to the theatre of his day. With The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana ( New York, 1859; Adel. 1861) and The Colleen Bawn; or, The Brides of Garryowen ( New York, 1860; Adel. 1860) a definite approach was made

towards reproducing the conditions of real life; in that life Boucicault discovered new material to exploit, new appeals which he might make to the public. Cleverly, however, he chose spheres of interest where he might freely introduce a flavour of romance, a dash of patriotic sentiment, a certain semblance of the real allied to a richness of spectacle. The Colleen Bawn, with its musical accompaniments, is thus obviously related to the older melodrama. In the printed text and in the original play-bills the scenic show is fully advertised; that was part of the appeal. At the same time this melodramatic basis and this pleasing spectacle are subtly related to actual existence; instead of wizards' caverns and vampires' dens The Colleen Bawn introduces us to the familiar made rosy and imaginative.

A similar combination of elements appears in The Octoroon. No one could fail to be impressed by the author's rich vitality and dramatic inventiveness. The love of George Peyton for Zoe, the octoroon; the poverty threatening Mrs Peyton; the villainies of McClosky; the apparent disasters and the ultimate triumph of good -- all these keep the plot moving swiftly. And again theatrical use is made of the life known to the audience. To us this use of material things may seem more than a trifle absurd and forced; but the sense of novelty which would accompany their original introduction must have amply compensated for any dim feeling of dissatisfaction. Take the camera episode. McClosky is the brutal villain of the regular melodramatic tradition, and in Act II he murders Paul, thinking that no eye has seen his crime. Unfortunately for him, however, a camera belonging to Scudder has been standing facing him all the time, and, as he is muttering "What a find! this infernal letter would have saved all", the stage direction declares that "he remains nearly motionless under the focus of camera". The result of this becomes apparent in the last scene.

=====The Theatre Handbook: And Digest of Plays by George Freedley, Bernard Sobel; Crown Publishers, 1940=====

Octoroon, The. Dion Boucicault (American). 5 act melodrama. 1859.

Zoe, the octoroon daughter of a plantation owner and a slave, is given her freedom by her father. Jacob McClosky, the villain, plots against and murders innocent people in order to get the beauty in his clutches.

He does manage to get her, after she loses her freedom, and is sold to him from the auction block for $25,000.00. But by the grace of Salem Scudder, a benign overseer, and an Indian who is seeking vengeance against the villain, Zoe is saved and the play has a happy ending.

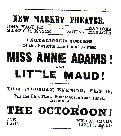

Morning Oregonian, Feb. 18, 1879 |

Morning Oregonian, Feb. 18, 1879 |

The first article is an ad for the play. Notice Maude Adams is "Little Maud" in the ad, and her mother has top billing. The second article, from the same paper, notes that Maude Adams did a good job in her performance.

|