The Jesters

The play, produced by Charles Frohman, opened January 15, 1908 at the Empire Theater. One source listed it as 'just not popular', although it did run for 53 performances.

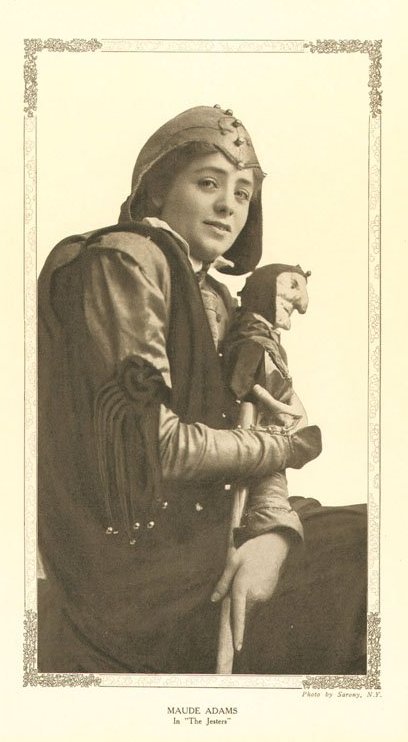

The play opened in New York on January 15, 1908 with Maude Adams playing the part of Chicot (another source listed the name as Rene), a 'dashing young nobleman disguised as a jester with a hump.' The play is set in sixteenth-century France. The nobleman has made a bet with a friend that it is wit and not beauty which is needed to gain a girl's love.

There were 53 performances in New York, then the play was taken on a short spring tour. Frohman said the play was not a financial success.

She performed in the play through the winter and early summer.

=====Charles Frohman:' Manager and Man by Issac F. Marcosson and Daniel Frohman, with an Appreciation by James M. Barrie. 1916=====

Having made such n enormous success with 'Peter Pan,' Miss Adams now turned to her third boy's part. It was that of 'Chicot, the Jester,' John Raphael's adaptation of Migue Zamaceis' play 'The Jesters.' This was a very delightful sort of Prince Charming play, fragile and artistic. The opposite part was played by Consuelo Bailey. It was a great triumph for Miss Adams, but not a very great financial success

Reviews

One of the reviews went like this:

'Miss Adams herself, playing with a fine sense of delicate values, gave to the figure of Chicot the charm of youth, high spirits, and sympathetic sensibility. She was a picture to look upon in a costume of cloth of gold, her trim and slender little figure moving lithely and gracefully through the play. Her characterization is in fact a very lovely thing.'

Another review:

'The change in speech, atmosphere, and mood in The Jesters from those of most of the plays of the winter was pleasant to feel, and the audience last night answered intently and warmly to it.'

Miss Adams herself, playing with a fine sense of delicate values, gave to the figure of Chicot the charm of youth, high spirits, and sympathetic sensibility. She was a picture to look upon in a costume of cloth of gold, her trim and slender little figure moving lithely and gracefully through the play, her richly pliant voice now gently sooting in the tend love passages, now manfully defiant when the deed of daring must be done. She has succeeded better than might have been expected in getting away from the manner of Peter Pan, a difficult matter in a role where to be a boy one must have boyish ways—and the Peter Pan way has seemed almost like second nature to this actress. But here her playing is nearer to the manner of her exquisite L'Aiglon, a role recalled especially during the poetic contest of 'The Jesters.'..Her characterization is in fact a very lovely thing, a thing to be seen often and to be remembered.1 New York Times, Jan. 16, 1908

Her delivery of verse was exceedingly ineffective. There were variations of force in her utterance, but none in her intonation, and the sentimental passages she chanted in a droning monotone. Evening Post, Jan. 16, 1908

'Miss Adams had not the vocal equipment to make the lines fly and ring. Many of her quickly rippled phrases were almost unintelligible at the back of the house.'' Second Nights, 1914

'The personal popularity of Miss Adams, which is tremendous and well earned, may carry it though to a sort of success. But this success will not be significant and the play will not be remembered.'' Sun, Jan. 16, 1908

'In all probability 'The Jesters' will take its place among the most successful plays in Miss Adam's repertory.'' Tribune, Jan. 16, 1908

=====The American Stage of To-Day by Walter Prichard Eaton; Small, Maynard and Company, 1908=====

With all due respect and admiration for Miss Maude Adams, with all due respect and admiration for the drama 'made in France' (a trade-mark supposed to carry all the weight of the English 'sterling'), with all due -- well, with all due consideration of the applause bestowed upon play and players, it is impossible to take 'The Jesters' very seriously. Putting aside for a moment the question of metrical form, the content and spirit of this play are spurious, and greatly to admire it, even greatly to derive pleasure from it, is to confuse the real with what is only imitation; to confuse, if not actually to debase, one's standards of taste and judgment; certainly to entangle one's merely friendly interest in the personality of Miss Adams with one's aesthetic appreciation of a work of art. Such a confusion of judgments is not, unfortunately, rare or difficult to fall into, and therein lies one of the greatest dangers of the 'star' system. The apparently considerable public approval of 'The Jesters' is an excellent case in point.

But 'The Jesters' has absolutely nothing whatever to say that has not already been said again and again, mostly better said, and mostly, for that matter, in 'Cyrano.' The play was originally produced by Sarah Bernhardt, and probably it was written for her. It isn't the first play that Sarah has disported herself in that had nothing to say, but it is one of a few that we remember which says nothing so tamely. Most of the others at least made a noise! The central idea of the piece, that of a Prince Charming disguised as a grotesque jester in order to court his lady love, might, indeed, conceivably yield to a resourceful playwright and to an actor like Coquelin or Mansfield considerable fun and a real situation or two. But, though we are told that Jacasse (or Chicot , as Miss Adams prefers to be called, fearing, no doubt, that a phonetic pronunciation would be accepted by her audiences in lieu of a translation!) worsts all his opponents in a jesting tournament, his victory is about as convincing as that of the young woman over the millionaire in 'The Lion and the Mouse.' Just as there the real effect was one of pity for the thick wits of the millionaire, so here one chiefly scorns the other jesters instead of admiring Jacasse (pardon, Chicot). And, of course, the presence of a woman in the rle is utterly destructive of any illusion during the so-called 'love scenes.' Boys may have played Juliet in Shakespeare's day, but girls cannot play Romeo now, unless they do it, as Ann did in 'Man and Superman,' by a complete reversal of the sexes.

Well, as with the little L'Aiglon, Miss Adams has once more assumed a male rle laid down by Sarah the Grand. She has rushed in where angles fear to tread. And nobody could look more charming and graceful in those frank masculine garments than she. Indeed she looks altogether too charming. As the grotesque jester, her hump alone is grotesque, and that is almost invisible. Any genuine effort to make the disguise stand out by contrast, any willingness on her part to sacrifice her personal charm for the demands of the play, is lacking. The demands, to be sure, are slight enough; it is no Rigoletto that she is called upon to impersonate, even in jest. If it were she could not do it. It is not lack of ability; it is lack either of understanding or of willingness to let her art stand higher than the easy appeal to the personal affections of a simpleminded public. The creation of illusion in a love passage is beyond her power as it is beyond that of any other woman player in a man's rle; and for this reason alone 'The Jesters' could never have more than a success of curiosity.

But a little something more than the simpering romance, the tame prettiness of the play as it is given here is possible. And that something is not lost through the clumsiness of Miss Adams's supporting company, which in most cases is considerable. It is lost through Miss Adams's own failure to forego the pretty and the romantic (I blush every time I am obliged to use that excellent word in connection with this play) and make herself externally unattractive and grotesque, perhaps in voice and manner as well as form and garb, in order to win what dramatic contrast and what faint echo of real romance the play might contain. Now, when Miss Adams takes the center of the stage, radiating that peculiar, elfin charm that has so endeared her to the public, looking as lovely as a picture, as graceful as a sylph, and recites her speech about the breeze, one thinks awhile of ugly old Cyrano and his speech below the balcony, and then, more and more, of Kipling's poem, till finally the devil whispers behind the scenes, 'It's pretty, but is it art?'

=====French Theatre in New York: A List of Plays, 1899-1939 by Hamilton Mason; Columbia University Press, 1940=====

The Jesters: Les Bouffons, Miguel Zamacois; adapter, John Raphael; producer, Charles Frohman; Empire Theatre; January 15, 1908; 52 performances; with Maude Adams (Ren de Chancenac), Mathilde Cotrelly (Nicole), Consuelo Bailey (Solange de Mautpr), Gustav von Seyffertitz (Vulcano), Fred Tyler (Baron de Mautpr), William Lewers, (Robert de Belfonte), Edwin Holt (Oliver), E. W. Morrison (Baroco), Frederic Eric (Hilarius), George H. Trader (Jack Pudding), Wallace Jackson (Jacques), Frederick Santley (Julian), L. B. Carleton (Pierre), William H. Claire (Hubert), T. C. Valentine (Pedlar).

Ren and Robert make a wager as to whether women prefer the spiritual or the physical. Disguised as peddlers, they go to Solange for her to decide the great question. Ren, now a hunchback, wins with his beautiful tale of the breeze. After Solange falls in love with him in spite of his deformity, Ren reveals his identity. Being impoverished, the proud baron, Solange's father, does not wish a marriage to occur. Legend has it that the castle grounds conceal a buried treasure chest. Ren takes care that one is found.

=====American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1869-1914 by Gerald Bordman; Oxford University Press, 1994=====

Maude Adams remained America's most beloved actress, so whatever profit Miguel Zamacos's The Jesters ( 1-15-08, Empire) reaped in its seven-week run probably was to her credit. In Paris, Bernhardt had triumphed in the play, but a number of reviewers felt the role of a prince who disguises himself as a hunchbacked fool to court a beautiful princess was unsuited to Miss Adams's more gentle, wistful art. One critic raised another objection: 'Many of her quickly rippled phrases were almost unintelligible at the back of the house, and her habit of changing vowels into curious diphthong sounds-'All my luck, I claim' into 'Ool my luck, I cle-eem'--did not add to the effect.'

The Mansfield News, Feb. 1, 1908 |

The Mansfield News, Feb. 26, 1908 |

Warren Evening Mirror, March 13, 1908 |

The second article (from the left), notes that this was her third male role and it also gives a short description of the play. The third article is one of the type where you get an idea of just how much she was liked.

|