Picnic at Hanging Rock review

Peter Weir scored the first of the year's hype-machine overkills this summer with The Truman Show, the story of an awakening individual who yearns to escape a repressed, rigidly controlled artificial environment. It's not the masterpiece its studio unwisely promoted it to be, but it is a clever and ingeniously directed film. And it ought to be: The Australian director had made a dry run for it 23 years before. Picnic at Hanging Rock, Weir's deeply unsettling 1975 film about a disappearance at a turn-of-the-century boarding school for girls, has just been given a new reissue; seen in Truman's cathode-ray glow, it's remarkably similar in both theme and style.

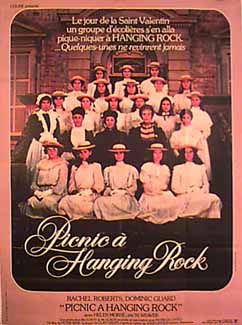

Picnic at Hanging Rock opens on Valentine's Day 1900 at stern Mrs. Appleyard's school, where the girls giggle in their rooms and read love poems until they're called downstairs for which they must lace each other into straitjacket-like corsets and assume identical outfits. On a morning expedition to nearby Hanging Rock, an uncharted formation of volcanic rock, four of the girls wander off to explore the summit. As if in a trance, they slip off their stockings and disappear into the rock's womb-like crevices. A few hours later, only one of the girls returns, and she's in a state of hysteria.

So what happened? The lack of a definite answer only contributes to the movie's somnambulant, feverish mood (as well as its fervent cult following). The key seems to be Miranda (Anne Lambert), a blossoming, vibrant girl who's repeatedly compared to "a Botticelli angel." Before she vanished, Miranda confided to a schoolmate that she wouldn't be around much longer; did she have a vision of a sinister fate? Or had she already planned her escape, Truman-style, from the school's repressive confines? The drab Appleyard school has none of the cheery pastels of Truman's Nick-at-Nite hometown, but it's just as stifling to the spirit, the libido, and the imagination's just as unnatural.

In Weir's movies, from The Last Wave through Fearless, nature weather, geography, fates beyond the control of man: Even the director's stand-in, Truman's creator Christof, gets a rude awakening when he thinks he's rigged the universe. At best, we're spectators; at worst, intruders. Just as Truman's every move is recorded by hundreds of hidden cameras, the girls in the woods are being watched by unseen eyes: There are several startling shots in Picnic that force us to consider what point of view we're taking. But in both films, the answer comes back: the voyeur's, the director's but never the creator's.

Fittingly, both Truman and Miranda escape to someplace neither the viewer nor the director is allowed to see. Weir holds out the hope or the threat that there's a realm of existence we can't just invade; that tantalizing possibility gives Picnic at Hanging Rock its mystical, hypnotic otherworldliness. Does Miranda vanish into thin air, or into cold, cold ground? Either way, you may keep returning to the haunting final shot for days. Judging from Peter Weir's subsequent work, he never fully left Hanging Rock either.

Back to start of Hanging Rock section

My Index Page

|