Picnic at Hanging Rock

(Australia, 1975, 110 minutes)

Direction: Peter Weir

Script: Cliff Green, based on the novel by Joan Lindsay

Cinematography: Russell Boyd

Music: J.S. Bach, Ludwig von Beethoven, Bruce Smeaton

Cast: Rachel Roberts, Dominic Guard, Helen Morse, Jacki Weaver,

Vivean Gray, Kirsty Child, Anne Lambert, Karen Robson, Jane Vallis,

Christine Schuler, Margaret Nelson, John Jarratt, Ingrid Mason,

Martin Vaughan, Jack Fegan, Wyn Roberts, Garry McDonald, Frank

Gunnell.

On St. Valentine's Day, 1900, a party of schoolgirls and their

teachers celebrate by going on a picnic excursion to a gigantic

volcanic rock, described as a "geological wonder" by their geometry

teacher, Miss McCraw. Three students and Miss McCraw disappear

without trace. The subsequent recovery of one girl, her apparent

amnesia, the questioning of various witnesses, and the marks on the

foreheads of several who survive the experience of being lost on the

rock lend an eerie edge to the tale.

A recurring theme in Peter Weir's oeuvre, the presence of the

unknown is perhaps most palpable in Picnic at Hanging Rock. Unlike

many filmmakers, Weir does not give the audience the distanced

perspective of omniscience; much like the characters, we are swept

into the mystery of what happened on the rock. The film's lush

imagery and just-beneath-the-surface eroticism add to its hypnotic

effect. From the opening scenes of the film, the atmosphere is

charged with semi-repressed sexual longing: students for students,

students for teachers, the gardener for the maid. The only characters

who act on their sexual feelings, the gardener and the maid, do so in

secret. The only character who openly expresses her feelings, Sara,

is somewhat of an outcast.

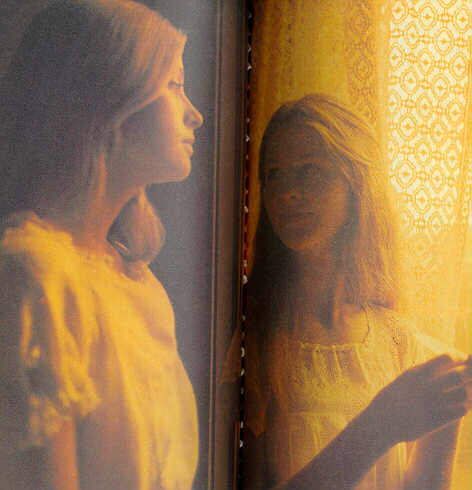

Many of the most striking images from the film's first half

involve the idea of a particular view; much like in The Double Life

of Veronique, we are made aware of the view's construction through

shots that show us the construction of an image (reflections, the

magnifying glass, the photo of Miranda). The most striking example of

this is the French teacher's comparison of Miranda to "a Botticelli

angel." When we see the Botticelli "angel," it turns out to be

Botticelli's famous painting of Venus, who is definitely not an

angel, particularly by Victorian standards.

For the most part, Picnic at Hanging Rock is set in two

contrasting locales: the school, a building of classical symmetry,

the ultimate controlled environment, and the rock, which seems alive

in its own right. Repeated shots of face-like outcroppings of the

rock, closeups of moving insects and reptiles (especially snakes,

associated with original sin), particularly while the schoolgirls are

asleep on the rock, and the wheeling flocks of birds give this

natural environment a wild, alien quality.

Interestingly, the film ends with the deaths of two characters who

did not go on the picnic: Sara throws herself from the school rooftop

and is discovered in the school greenhouse (!), while Mrs. Appleyard

is apparently rejected by the rock, since her body is discovered, in

contrast to the other characters. Although Weir does not give much

time to on-screen speculation about what happened to the individuals

who disappeared on the rock, the one possibility that is

mentioned--abduction--plants the seed of the idea that the rock

itself abducted them.

Fearless (1993); Green Card (1990); Dead Poets Society (1989); The

Mosquito Coast (1986); Witness (1985); The Year of Living Dangerously

(1983); Gallipoli (1981); The Plumber (1979); The Last Wave (1977);

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975); The Cars That Ate Paris (1974).

--film notes by Heather Inman

Back to start of Picnic at Hanging Rock section

My Index Page

|